21 Ideas I Learned From Reading The Black Swan (by Nassim Taleb)

21 Nuggets by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

👋 Hey friend,

In today’s letter, I share the 21 ideas I picked from reading (actually, re-reading) The Black Swan, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

I think this is one of these books that I wanna re-read every few years. Not only because I find the information extremely valuable (to make better decisions in the real world), but also because it’s a pleasure to read it — it’s written as a novel (with fictional characters and great humor).

“I would rather read the best 100 books over and over again until I absorb them rather than read all the books.”

- Naval Ravikant

So I decided to re-read The Black Swan last month, and here are my 21 favorite ideas from the book (with personal reflections).

By the way, I also made it into a 🎧 podcast episode (with a manually written transcription on-screen). So if you prefer to listen, open any of the links below to listen on your favorite podcast app…

YouTube (with perfect transcription on-screen):

Spotify (with perfect transcription on-screen):

Apple Podcasts:

👤 Doers

💡Introduction

At the beginning of the book, Nassim tells why this particular type of bird — the black swan — is representative of the central idea in this book…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Before the discovery of Australia, people in the Old World were convinced that all swans were white, an unassailable belief as it seemed completely confirmed by empirical evidence. The sighting of the first black swan might have been an interesting surprise for a few ornithologists (and others extremely concerned with the coloring of birds), but that is not where the significance of the story lies. It illustrates a severe limitation to our learning from observations or experience and the fragility of our knowledge. One single observation can invalidate a general statement derived from millennia of confirmatory sightings of millions of white swans. All you need is one single (and, I am told, quite ugly) black bird.

What we call here a Black Swan is an event with the following three attributes.

First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility.

Second, it carries an extreme impact (unlike the bird).

Third, in spite of its outlier status, human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.

I stop and summarize the triplet: rarity, extreme impact, and retrospective predictability.

We can have negative black swans, where you are hurt by uncertainty, and positive black swans, where you are benefited from uncertainty…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Black Swans being unpredictable, we need to adjust to their existence (rather than naïvely try to predict them). There are so many things we can do if we focus on antiknowledge, or what we do not know. Among many other benefits, you can set yourself up to collect serendipitous Black Swans (of the positive kind) by maximizing your exposure to them. Indeed, in some domains—such as scientific discovery and venture capital investments—there is a disproportionate payoff from the unknown, since you typically have little to lose and plenty to gain from a rare event. We will see that, contrary to social-science wisdom, almost no discovery, no technologies of note, came from design and planning—they were just Black Swans. The strategy for the discoverers and entrepreneurs is to rely less on top-down planning and focus on maximum tinkering and recognizing opportunities when they present themselves. So I disagree with the followers of Marx and those of Adam Smith: the reason free markets work is because they allow people to be lucky, thanks to aggressive trial and error, not by giving rewards or “incentives” for skill. The strategy is, then, to tinker as much as possible and try to collect as many Black Swan opportunities as you can.

On this idea of collecting positive black swan opportunities, i remember a tweet from Naval Ravikant where he made his own list of asymmetric opportunities.

Now, let’s dive into the 21 ideas I picked from reading The Black Swan…

💡Idea #1: Focus on the Outliers

Taleb argues that the right way to study phenomena is to focus on the extremes and the outliers, rather than focusing on the ordinary non-consequential observations.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

There are two possible ways to approach phenomena. The first is to rule out the extraordinary and focus on the “normal.” The examiner leaves aside “outliers” and studies ordinary cases. The second approach is to consider that in order to understand a phenomenon, one needs first to consider the extremes—particularly if, like the Black Swan, they carry an extraordinary cumulative effect.

I don’t particularly care about the usual. If you want to get an idea of a friend’s temperament, ethics, and personal elegance, you need to look at him under the tests of severe circumstances, not under the regular rosy glow of daily life. Can you assess the danger a criminal poses by examining only what he or she does on an ordinary day? Can we understand health without considering wild diseases and epidemics? Indeed the normal is often irrelevant.

Almost everything in social life is produced by rare but consequential shocks and jumps; all the while almost everything studied about social life focuses on the “normal,” particularly with “bell curve” methods of inference that tell you close to nothing. Why? Because the bell curve ignores large deviations, cannot handle them, yet makes us confident that we have tamed uncertainty. Its nickname in this book is GIF, Great Intellectual Fraud.

This idea from Taleb of focusing on the outliers reminds me of something that Warren Buffet said on the 1998 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting...

🟠 Warren Buffett:

The word “anomaly” I have always found interesting—what it means is something that the academicians could not explain. And rather than re-examine their theories they simply just discard any evidence of that sort as “anomalous”. I mean… Columbus was an “anomaly.” I think when you find information that contradicts previously cherished beliefs… You’ve got a special obligation to look at it and look at it quickly.

👉 Source: 1998 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting - Full Version

Elon Musk also has his own version of this idea. He says that in order to understand things, an important tool is to test things to the limit—which means to focus on the extremes.

🟠 Elon Musk:

Another good physics tool is thinking about things in the limit. If you take a particular thing and you scale it to a very large number or to a very small number… How do things change? Take the example of Manufacturing—which I think is a very underrated problem. So let’s say you are trying to figure out Why is this product expensive?

[1] Is it because of something fundamentally foolish that we’re doing?

Or [2] Is it because our volume is too low? So then you say: What if our volume was a million units / year? Is it still expensive? That’s what I mean by thinking about things to the limit. If it’s still expensive at a million units / year… then volume is not the reason why your thing is expensive. There’s something fundamental about the design. So [then] you change the design/part to be something that is not fundamentally expensive. That’s a common thing in Rocketry. Because the unit volume is relatively low and so a common excuse would be: “Well it’s expensive because our unit volume is low. And if we were in the Automotive [industry] or Consumer Electronics then our costs would be lower.” And I’m like… “Okay. So let’s say that now we are making a million units / year. Is it still expensive? If the answer is yes, then Economies of Scale are not the issue.”

👉 Source: Elon Musk | How to Solve any Problem (A Unique and Powerful Approach)

So in that example from Elon Musk we can see clearly how taking something to its limit or extreme is a great way to gain insight about a problem.

💡Idea #2: Platonicity

Taleb calls “Platonicity” the world of crisp forms and theoretical models, which contrasts heavily with the real world — where forms are not crisp and the way it works is too complex to model.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

What I call Platonicity, after the ideas (and personality) of the philosopher Plato, is our tendency to mistake the map for the territory, to focus on pure and well-defined “forms,” whether objects, like triangles, or social notions, like utopias (societies built according to some blueprint of what “makes sense”), even nationalities. When these ideas and crisp constructs inhabit our minds, we privilege them over other less elegant objects, those with messier and less tractable structures.

Platonicity is what makes us think that we understand more than we actually do. But this does not happen everywhere. I am not saying that Platonic forms don’t exist. Models and constructions, these intellectual maps of reality, are not always wrong; they are wrong only in some specific applications. The difficulty is that

a) you do not know beforehand (only after the fact) where the map will be wrong, and

b) the mistakes can lead to severe consequences. These models are like potentially helpful medicines that carry random but very severe side effects.

The Platonic fold is the explosive boundary where the Platonic mind-set enters in contact with messy reality, where the gap between what you know and what you think you know becomes dangerously wide. It is here that the Black Swan is produced.

So my takeaway here is that it is useful to learn mental maps but one should never take them as if they were a full representation of reality. Because reality is always more complex.

So if we can learn mental maps while being open-minded, i think that’s the key. And of course as you learn more or you get feedback from reality you can also upgrade your mental maps. For instance, if you first thought that risks in the economy can be model with the bell curve distribution, you’ll realize either by experience or by reading The Black Swan or listening to Charlie Munger that risks actually follow a power law distribution.

The great economist and hedge fund manager Ray Dalio has also talked about this relationship between mental maps and open-mindedness.

🟠 Ray Dalio:

Imagine rating from one to ten how good someone’s mental map is on the Y-axis and how humble or open-minded they are on the X-axis.

Everyone starts out in the lower left area, with poor mental maps and little open-mindedness, and most people remain tragically and arrogantly stuck in that position. You can improve by either going up on the mental-maps axis (by learning how to do things better) or out on the open-mindedness axis. Either will provide you with better knowledge of what to do. If you have good mental maps and low open-mindedness, that will be good but not great. You will still miss a lot that is of value. Similarly, if you have high open-mindedness but bad mental maps, you will probably have challenges picking the right people and points of view to follow. The person who has good mental maps and a lot of open-mindedness will always beat out the person who doesn’t have both.

Now take a minute to think about your path to becoming more effective. Where would you place yourself on this chart? Ask others where they’d place you.

Once you understand what you’re missing and gain open-mindedness that will allow you to get help from others, you’ll see that there’s virtually nothing you can’t accomplish.

👉 Book: Principles, by Ray Dalio

💡Idea #3: The Anti-Library

The next story offers an interesting solution to protect yourself against negative black swans. The solution is to build what Taleb calls an “antilibrary”.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The writer Umberto Eco belongs to that small class of scholars who are encyclopedic, insightful, and nondull. He is the owner of a large personal library (containing thirty thousand books), and separates visitors into two categories: those who react with “Wow! Signore professore dottore Eco, what a library you have! How many of these books have you read?” and the others—a very small minority—who get the point that a private library is not an ego-boosting appendage but a research tool. Read books are far less valuable than unread ones. The library should contain as much of what you do not know as your financial means, mortgage rates, and the currently tight real-estate market allow you to put there. You will accumulate more knowledge and more books as you grow older, and the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at you menacingly. Indeed, the more you know, the larger the rows of unread books. Let us call this collection of unread books an antilibrary.

We tend to treat our knowledge as personal property to be protected and defended. It is an ornament that allows us to rise in the pecking order. So this tendency to offend Eco’s library sensibility by focusing on the known is a human bias that extends to our mental operations. People don’t walk around with anti-résumés telling you what they have not studied or experienced (it’s the job of their competitors to do that), but it would be nice if they did. Just as we need to stand library logic on its head, we will work on standing knowledge itself on its head. Note that the Black Swan comes from our misunderstanding of the likelihood of surprises, those unread books, because we take what we know a little too seriously.

Let us call an antischolar a skeptical empiricist. Someone who focuses on the unread books, and makes an attempt not to treat his knowledge as a treasure, or even a possession, or even a self-esteem enhancement device.

Charlie Munger has a great line on this idea of not treating your knowledge as a treasure: “Any year that passes in which you don’t destroy one of your best loved ideas is a wasted year.”

And the co-founder of Airbnb Brian Chesky also talks about this idea of never settling with what you currently know, and always being in a place of becoming...

🟠 Brian Chesky:

I think that that is the key. It’s learning, it’s growing, it’s curiosity, it’s constantly having that hunger and that fire to always want to be better, to feel like I haven’t made it yet.

The reason I say I haven’t made it yet is because if I’ve made it, then I’m done.

And I want to feel like an artist. Bob Dylan used to say an artist has to be in a constant place of becoming. And so long as they don’t become something, then they’re gonna be okay.

💡Idea #4: Scalable and non-scalable professions

Taleb classifies professional careers in 2 types: the scalable profession and the non-scalable profession.

The scalable profession is black-swan driven, and here you get paid by the quality of your decisions rather than your time and labor. So you don’t need to be working all the time. As an example, think of book authors. If you are a successful author, you obviously don’t need to labour like an accountant would have to. But of course the nuance is that is very hard to be a successful book author — there is only a very small minority that win at that game. It takes a black swan of the positive kind to be successful at a scalable profession.

The other type, the non-scalable profession, doesn’t have black swans. Here you get paid by the hour, and it demands continuous effort and labor. As an example, just think of any employee who gets paid a monthly salary. Be it an accountant or a baker.

Taleb says that in scalable professions you have the idea person — who sells an intellectual product in the form of a transaction or a piece of work. Whereas in non-scalable professions you have the labor person — who sells you his work…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

If you are an idea person, you do not have to work hard, only think intensely. You do the same work whether you produce a hundred units or a thousand. In quant trading, the same amount of work is involved in buying a hundred shares as in buying a hundred thousand, or even a million. It is the same phone call, the same computation, the same legal document, the same expenditure of brain cells, the same effort in verifying that the transaction is right. Furthermore, you can work from your bathtub or from a bar in Rome. You can use leverage as a replacement for work! Well, okay, I was a little wrong about trading: one cannot work from a bathtub, but, when done right, the job allows considerable free time.

The same property applies to recording artists or movie actors: you let the sound engineers and projectionists do the work; there is no need to show up at every performance in order to perform. Similarly, a writer expends the same effort to attract one single reader as she would to capture several hundred million. J. K. Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter books, does not have to write each book again every time someone wants to read it. But this is not so for a baker: he needs to bake every single piece of bread in order to satisfy each additional customer.

So the distinction between writer and baker, speculator and doctor, fraudster and prostitute, is a helpful way to look at the world of activities. It separates those professions in which one can add zeroes of income with no greater labor from those in which one needs to add labor and time (both of which are in limited supply)—in other words, those subjected to gravity.

Naval Ravikant also talks about leverage in careers...

🟠 Naval Ravikant:

There are three broad classes of leverage:

One form of leverage is labor—other humans working for you. It is the oldest form of leverage, and actually not a great one in the modern world. [1] I would argue this is the worst form of leverage that you could possibly use. Managing other people is incredibly messy. It requires tremendous leadership skills. You’re one short hop from a mutiny or getting eaten or torn apart by the mob.

Money is good as a form of leverage. It means every time you make a decision, you multiply it with money. Capital is a trickier form of leverage to use. It’s more modern. It’s the one that people have used to get fabulously wealthy in the last century. It’s probably been the dominant form of leverage in the last century. You can see this by looking for the richest people. It’s bankers, politicians in corrupt countries who print money, essentially people who move large amounts of money around. If you look at the top of very large companies, outside of technology companies, in many, many large old companies, the CEO job is really a financial job. It scales very, very well. If you get good at managing capital, you can manage more and more capital much more easily than you can manage more and more people.

The final form of leverage is brand new—the most democratic form. It is: “products with no marginal cost of replication.” This includes books, media, movies, and code. Code is probably the most powerful form of permissionless leverage. All you need is a computer—you don’t need anyone’s permission.

The most interesting and the most important form of leverage is the idea of products that have no marginal cost of replication. This is the new form of leverage. This was only invented in the last few hundred years. It started with the printing press. It accelerated with broadcast media, and now it’s really blown up with the internet and with coding. Now, you can multiply your efforts without involving other humans and without needing money from other humans.

Taleb also warns us about the scalable professions. He says that a scalable profession is only good if you’re successful. And is way harder to be successful at a scalable profession compared to a non-scalable profession. He said: “If I myself had to give advice, I would recommend someone pick a profession that is not scalable!”

Now this book was published in 2007, so it doesn’t take much in consideration this latest form of leverage which is code and content creation on the internet. And although is true that it’s also very hard to be successful as a programmer making your own products or a content creator, we have definitely seen a huge rise in the number of people that are now making a living as an idea person by coding or making content on the internet.

This differentiation of scalable and non-scalable happens because we have 2 types of uncertainties, 2 types of randomness. On the scalable side we have the black swan type of uncertainty — which we have seen is rare and consequential. And on the non-scalable side, we have things that we can model with the bell curve — where there might be rare events but these are inconsequential to the aggregate.

And to expand on this fundamental distinction of uncertainties, Taleb comes up with two utopian provinces. The province of Mediocristan — where we have purely the non-scalable. And the province of Extremistan — where we have purely the scalable.

💡Idea #5: The Province of Mediocristan

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Let’s play the following thought experiment. Assume that you round up a thousand people randomly selected from the general population and have them stand next to one another in a stadium.

Imagine the heaviest person you can think of and add him to that sample. Assuming he or she weighs three times the average, between four hundred and five hundred pounds, he or she will rarely represent more than a very small fraction of the weight of the entire population (in this case, about a half of a percent). You can get even more aggressive. If you picked the heaviest biologically possible human on the planet (who yet can still be called a human), he or she would not represent more than, say, 0.6 percent of the total, a very negligible increase. And if you had ten thousand persons, the contribution of the heaviest of the heavy would be vanishingly small.

In the utopian province of Mediocristan, particular events don’t contribute much individually—only collectively. I can state the supreme law of Mediocristan as follows: When your sample is large, no single instance will significantly change the aggregate or the total. The largest observation will remain impressive, but eventually insignificant, to the sum.

Taleb also gives the example of caloric consumption. No matter how much you eat in a single day, it will still be an insignificant amount when we compare it with the total of calories that a human can eat in a year. So things like caloric consumption and human weight are domains that belong to the country of Mediocristan, where no single observation can be significant to the sum total of observations.

Other areas from Mediocristan that Taleb mentions are height, income for a baker, a small restaurant owner, a prostitute, or an orthodontist, then we have car accidents, mortality rates, and IQ (as measured).

💡Idea #6: The Province of Extremistan

Some examples that Taleb uses here are wealth and book sales. On wealth he tells that if you put together 1,000 random people and then you add Bill Gates, what happens is that Bill Gates’s wealth would be over 99.99% of the total wealth of all the people. And in a group of 1,000 random book authors, J.K. Rowling alone would have over 99.99% of the total volume of book sales. So as we see, one single observation can contribute to most of the output in the world of Extremistan.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

In Extremistan, inequalities are such that one single observation can disproportionately impact the aggregate, or the total.

So while weight, height, and calorie consumption are from Mediocristan, wealth is not. Almost all social matters are from Extremistan. Another way to say it is that social quantities are informational, not physical: you cannot touch them. Money in a bank account is something important, but certainly not physical. As such it can take any value without necessitating the expenditure of energy. It is just a number!

Note that before the advent of modern technology, wars used to belong to Mediocristan. It is hard to kill many people if you need to slaughter them one at the time. Today, with tools of mass destruction, all it takes is a button, a nutcase, or a small error to wipe out the planet.

Look at the implication for the Black Swan. Extremistan can produce Black Swans, and does, since a few occurrences have had huge influences on history. This is the main idea of this book.

On things that belong to Extremistan, Taleb also mentions academic citations, media references, income, company size, name recognition as a celebrity, populations of cities, uses of words in a vocabulary, numbers of speakers per language, damage caused by earthquakes, deaths in war, size of planets, stock ownership, financial markets, and so on.

The renowned entrepreneur and investor Peter Thiel also says in his book Zero to One: “We do not live in a normal world, we live under a power law.” And in this context the word “normal” represents the gaussian or Mediocristan, whereas the power law represents Extremistan. A power law is simply the probability distribution that belongs to Extremistan.

💡Idea #7: The Problem of Induction

One of the big problems in the world of Extremistan is the Problem of Induction—where people observe specific instances and then, based on that, they come up with a general conclusion.

To illustrate this problem, Taleb tells the story of the turkey.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird’s belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race quote unquote “looking out for its best interests,” as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, something unexpected will happen to the turkey. It will incur a revision of belief.

The rest of this chapter will outline the Black Swan problem in its original form: How can we know the future, given knowledge of the past; or, more generally, how can we figure out properties of the (infinite) unknown based on the (finite) known? Think of the feeding again: What can a turkey learn about what is in store for it tomorrow from the events of yesterday? A lot, perhaps, but certainly a little less than it thinks, and it is just that “little less” that may make all the difference.

The turkey problem can be generalized to any situation where the same hand that feeds you can be the one that wrings your neck.

So the turkey problem shows that learning from the past or learning from observations can be false, irrelevant, and even misleading. Learning from empirical data is very useful in Mediocristan—where the collective rules—but in the black-swan driven world of Extremistan, is dangerous to reach a general conclusion from the observable data. Because one single data point can change everything.

Another example that Taleb gives is the long period of peace since the Napoleonic conflicts, which led people to believe in the disappearance of big wars, but then The Great War happened and took everybody by surprise.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Mistaking a naïve observation of the past as something definitive or representative of the future is the one and only cause of our inability to understand the Black Swan.

Those who believe in the unconditional benefits of past experience should consider this pearl of wisdom allegedly voiced by a famous ship’s captain:

“But in all my experience, I have never been in any accident… of any sort worth speaking about. I have seen but one vessel in distress in all my years at sea. I never saw a wreck and never have been wrecked nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in a disaster of any sort.” - E.J. Smith, captain of RMS Titanic.

Captain Smith’s ship sank in 1912 in what became the most talked-about shipwreck in history.

💡Idea #8: Black Swans are Always Relative to Knowledge

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

From the standpoint of the turkey, the nonfeeding of the Wednesday afternoon before Thanksgiving is a Black Swan. For the butcher, it is not, since its occurrence is not unexpected. So you can see here that the Black Swan is a sucker’s problem. In other words, it occurs relative to your expectation. You realize that you can eliminate a Black Swan by science (if you’re able), or by keeping an open mind. Of course you can also create Black Swans with science, by giving people confidence that the Black Swan cannot happen—this is when science turns normal citizens into suckers.

💡Idea #9: The Round-trip Fallacy

This is a problem that stems from the original problem of induction, where people make assumptions and general conclusions from the visible data. And the round-trip fallacy happens when people confuse the statement “no evidence of black swans” with “evidence of no black swans”.

And I know it sounds confusing, but Taleb gives an illustration that explains this perfectly. He uses the example of cancer detection…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Take doctors examining a patient for signs of cancer; tests are typically done on patients who want to know if they are cured or if there is “recurrence.” (In fact, recurrence is a misnomer; it simply means that the treatment did not kill all the cancerous cells and that these undetected malignant cells have started to multiply out of control.)

It is not feasible, in the present state of technology, to examine every single one of the patient’s cells to see if all of them are nonmalignant, so the doctor takes a sample by scanning the body with as much precision as possible. Then she makes an assumption about what she did not see.

I was once taken aback when a doctor told me after a routine cancer checkup, “Stop worrying, we have evidence of cure.” “Why?” I asked. “There is evidence of no cancer” was the reply. “How do you know?” I asked. He replied, “The scan is negative.” Yet he went around calling himself doctor!

An acronym used in the medical literature is NED, which stands for No Evidence of Disease. There is no such thing as END, Evidence of No Disease. Yet my experience discussing this matter with plenty of doctors, is that many slip into the round-trip fallacy during conversation.

We can also see the round-trip fallacy in the Turkey problem. It would be correct if, before thanksgiving, the turkey says that there is no evidence of the possibility of a black swan event. But it would be incorrect if the turkey said instead that there is evidence of no possibility of a black swan event.

💡Idea #10: The Error of Confirmation (aka THE CONFIRMATION BIAS)

This is our tendency to look for data that confirms our belief or hypothesis, while disregarding the data that disconfirms it. The problem here is that this is the opposite of science. In science, we would try to falsify a hypothesis—that is, to try to find that disconfirmatory evidence. Because disconfirmatory evidence gives us much more knowledge than confirmatory evidence…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

If I see a black swan I can certify that all swans are not white! If I see someone kill, then I can be practically certain that he is a criminal. If I don’t see him kill, I cannot be certain that he is innocent. The same applies to cancer detection: the finding of a single malignant tumor proves that you have cancer, but the absence of such a finding cannot allow you to say with certainty that you are cancer-free.

We can get closer to the truth by negative instances, not by verification! It is misleading to build a general rule from observed facts. Contrary to conventional wisdom, our body of knowledge does not increase from a series of confirmatory observations, like the turkey’s. But there are some things I can remain skeptical about, and others I can safely consider certain. This makes the consequences of observations one-sided. It is not much more difficult than that.

…

Karl Popper generated a large-scale theory around this asymmetry, based on a technique called “falsification” (to falsify is to prove wrong) meant to distinguish between science and nonscience. This idea about the asymmetry of knowledge is so liked by practitioners, because it is obvious to them; it is the way they run their business.

And just to add another perspective to this idea, here’s a quote from Warren Buffett…

🟠 Warren Buffett:

I think when you find information that contradicts previously cherished beliefs… You’ve got a special obligation to look at it and look at it quickly.

I think Charlie [Munger] told me that one of the things [Charles] Darwin did was that whenever he found out anything that contradicted some previous belief, he knew he had to write it down almost immediately because he felt that the human mind was conditioned—so conditioned—to reject contradictory evidence that unless he got it down in black and white very quickly his mind would simply push it out of existence.

👉 Source: 1998 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting - Full Version

💡Idea #11: The Basis for True Self-Confidence

Taleb mentions how this process of looking for disconfirming evidence is perhaps the basis for true self-confidence, since it takes a great deal of confidence to try to prove your ideas wrong.

Taleb gives the example of the speculator George Soros, who, when making a financial bet, keeps looking for instances that would prove his initial theory wrong.

Ray Dalio has also talked about this on his book Principles.

🟠 Ray Dalio:

To be effective you must not let your need to be right be more important than your need to find out what’s true. If you are too proud of what you know or of how good you are at something you will learn less, make inferior decisions, and fall short of your potential.

…

If you’re like most people, you have no clue how other people see things and aren’t good at seeking to understand what they are thinking, because you’re too preoccupied with telling them what you yourself think is correct. In other words, you are closed-minded; you presume too much. This closed-mindedness is terribly costly; it causes you to miss out on all sorts of wonderful possibilities and dangerous threats that other people might be showing you—and it blocks criticism that could be constructive and even lifesaving.

👉 Book: Principles

So here again we can see how being open-minded is an incredibly useful trait in order to not only avoid negative black swans but also to benefit from black swans of the positive kind.

And to be open-minded, you need to have self-confidence, a confidence that is not dependent on what others think of you but on what you think of yourself.

There’s also another dimension on this topic of self-confidence that Taleb talks about…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Humans will believe anything you say provided you do not exhibit the smallest shadow of diffidence; like animals, they can detect the smallest crack in your confidence before you express it. The trick is to be as smooth as possible in personal manners. It is much easier to signal self-confidence if you are exceedingly polite and friendly; you can control people without having to offend their sensitivity. The problem with business people, Nero realized —[and Nero is a fictional character on this book]— is that if you act like a loser they will treat you as a loser—you set the yardstick yourself. There is no absolute measure of good or bad. It is not what you are telling people, it is how you are saying it.

Another perspective on this idea comes from the book The 48 Laws of Power (written by Robert Greene.) Law 34: BE ROYAL IN YOUR OWN FASHION: ACT LIKE A KING TO BE TREATED LIKE ONE. And to illustrate this law, Robert Greene uses the example of Christopher Columbus…

🟠 Robert Greene:

As an explorer Columbus was mediocre at best. He knew less about the sea than did the average sailor on his ships, could never determine the latitude and longitude of his discoveries, mistook islands for vast continents, and treated his crew badly. But in one area he was a genius: He knew how to sell himself. How else to explain how the son of a cheese vendor, a low-level sea merchant, managed to ingratiate himself with the highest royal and aristocratic families?

Columbus had an amazing power to charm the nobility, and it all came from the way he carried himself. He projected a sense of confidence that was completely out of proportion to his means. Nor was his confidence the aggressive, ugly self-promotion of an upstart—it was a quiet and calm self-assurance. In fact it was the same confidence usually shown by the nobility themselves. The powerful in the old-style aristocracies felt no need to prove or assert themselves; being noble, they knew they always deserved more, and asked for it. With Columbus, then, they felt an instant affinity, for he carried himself just the way they did—elevated above the crowd, destined for greatness.

Understand: It is within your power to set your own price. How you carry yourself reflects what you think of yourself. If you ask for little, shuffle your feet and lower your head, people will assume this reflects your character. But this behavior is not you—it is only how you have chosen to present yourself to other people. You can just as easily present the Columbus front: buoyancy, confidence, and the feeling that you were born to wear a crown.

“With all great deceivers there is a noteworthy occurrence to which they owe their power. In the actual act of deception they are overcome by belief in themselves: it is this which then speaks so miraculously and compellingly to those around them.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, 1844–1900

💡Idea #12: The Narrative Fallacy

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The fallacy is associated with our vulnerability to overinterpretation and our predilection for compact stories over raw truths. It severely distorts our mental representation of the world; it is particularly acute when it comes to the rare event.

The narrative fallacy addresses our limited ability to look at sequences of facts without weaving an explanation into them, or, equivalently, forcing a logical link, an arrow of relationship, upon them. Explanations bind facts together. They make them all the more easily remembered; they help them make more sense. Where this propensity can go wrong is when it increases our impression of understanding.

So in the processing of information, we have this biological tendency to look for causality. Because it helps us make sense of the data. But this doesn’t give us a real understanding, rather it gives us the illusion of understanding—which is actually more dangerous than ignorance. As Stephen Hawkins said: “The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge”. And of course in an increasingly more complex and black-swan driven world, this illusion of understanding is also increasingly more dangerous.

Taleb also argues that this tendency to simplify, seek patterns and rules, reduce the dimensionality of matters, and put order; makes us more likely to underestimate the role of randomness — since randomness represents disorder and the full dimensionality of matters. Therefore, Nassim Taleb says “The Black Swan is what we leave out of simplification.”

So… Is there a way to escape the narrative fallacy? Taleb argues that there is a way. By making conjectures and running experiments. By making testable predictions…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The way to avoid the ills of the narrative fallacy is to favor experimentation over storytelling, experience over history, and clinical knowledge over theories.

Being empirical does not mean running a laboratory in one’s basement: it is just a mind-set that favors a certain class of knowledge over others. I do not forbid myself from using the word cause, but the causes I discuss are either bold speculations (presented as such) or the result of experiments, not stories.

Another approach is to predict and keep a tally of the predictions.

Finally, there may be a way to use a narrative—but for a good purpose. Only a diamond can cut a diamond; we can use our ability to convince with a story that conveys the right message—what storytellers seem to do.

On that last idea about using stories to convey the right message, I just wanna add a famous line by Steve Jobs where he said: “The story-teller is the most powerful person in the room.”

Also the author and NYU professor Scott Galloway said that if his children could learn one skill it would be — hands down — story-telling. Because your ability to convince people comes down to story-telling. And he says that that is the premier skill among the most successful people.

💡Idea #13: Silent Evidence

Another fallacy in the way we understand events is that of silent evidence.

To easily understand this fallacy, Taleb uses the story of the drowned worshippers.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

More than two thousand years ago, the Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero, presented the following story. One Diagoras, a nonbeliever in the gods, was shown painted tablets bearing the portraits of some worshippers who prayed, then survived a subsequent shipwreck. The implication was that praying protects you from drowning. Diagoras asked, “Where were the pictures of those who prayed, then drowned?”

The drowned worshippers, being dead, would have a lot of trouble advertising their experiences from the bottom of the sea. This can fool the casual observer into believing in miracles.

We call this the problem of silent evidence. The idea is simple, yet potent and universal.

Taleb argues that the problem of silent evidence is very acute in Extremistan, because the few that win are visible and we hear about them, while we never hear of the cemetery of losers.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The neglect of silent evidence is endemic to the way we study comparative talent, particularly in activities that are plagued with winner-take-all attributes. We may enjoy what we see, but there is no point reading too much into success stories because we do not see the full picture.

Taleb gives the real-life example of the business of selling recipes for becoming a millionaire…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Numerous studies of millionaires aimed at figuring out the skills required for hotshotness follow the following methodology. They take a population of hotshots, those with big titles and big jobs, and study their attributes. They look at what those big guns have in common: courage, risk taking, optimism, and so on, and infer that these traits, most notably risk taking, help you to become successful.

Now take a look at the cemetery. It is quite difficult to do so because people who fail do not seem to write memoirs, and, if they did, those business publishers I know would not even consider giving them the courtesy of a returned phone call. Readers would not pay $26.95 for a story of failure, even if you convinced them that it had more useful tricks than a story of success.

The entire notion of biography is grounded in the arbitrary ascription of a causal relation between specified traits and subsequent events. Now consider the cemetery. The graveyard of failed persons will be full of people who shared the following traits: courage, risk taking, optimism, et cetera. Just like the population of millionaires. There may be some differences in skills, but what truly separates the two is for the most part a single factor: luck. Plain luck.

As a thought experiment to demonstrate this you can imagine a big enough sample of entrepreneurs or hedge funds, and when you consider this initial sample then it is almost certain that you are gonna have a few outliers that have a streak of good luck. So in order to avoid the distortion caused by the silent evidence, we should always consider the initial size of the sample—instead of focusing exclusively on the survivors or the winners.

And although it may seem that Taleb is telling us here to not take risks, this is actually not true…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

I am not dismissing the idea of risk taking, having been involved in it myself. I am only critical of the encouragement of uninformed risk taking. The überpsychologist Danny Kahneman has given us evidence that we generally take risks not out of bravado but out of ignorance and blindness to probability!

💡Idea #14: The Ludic Fallacy

The word ludic comes from ludus in latin, which means games. The Ludic Fallacy happens because there’s a huge difference between the attributes of uncertainty in games and exams, and the attributes of uncertainty in real life. And people who fall for the ludic fallacy are essentially suckers who treat the uncertainty of real life as if it was the same type of uncertainty found in an exam or a game in the casino.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

In the casino you know the rules, you can calculate the odds, and the type of uncertainty we encounter there is mild, belonging to Mediocristan.

The casino is the only human venture I know where the probabilities are known, Gaussian (i.e., bell-curve), and almost computable. You cannot expect the casino to pay out a million times your bet, or to change the rules abruptly on you during the game—there are never days in which “36 black” is designed to pop up 95 percent of the time.

In real life you do not know the odds; you need to discover them, and the sources of uncertainty are not defined.

I recently looked at what college students are taught under the subject of chance and came out horrified; they were brainwashed with this ludic fallacy and the outlandish bell curve. The same is true of people doing PhD’s in the field of probability theory. I’m reminded of a recent book by a thoughtful mathematician, Amir Aczel, called Chance. Excellent book perhaps, but like all other modern books it is grounded in the ludic fallacy.

Now, go read any of the classical thinkers who had something practical to say about the subject of chance, such as Cicero, and you find something different: a notion of probability that remains fuzzy throughout, as it needs to be, since such fuzziness is the very nature of uncertainty. Probability is a liberal art; it is a child of skepticism, not a tool for people with calculators on their belts to satisfy their desire to produce fancy calculations and certainties. Before Western thinking drowned in its “scientific” mentality, what is arrogantly called the Enlightenment, people prompted their brain to think—not compute. In a beautiful treatise now vanished from our consciousness, Dissertation on the Search for Truth, published in 1673, the polemist Simon Foucher exposed our psychological predilection for certainties. He teaches us the art of doubting, how to position ourselves between doubting and believing. He writes: “One needs to exit doubt in order to produce science—but few people heed the importance of not exiting from it prematurely.… It is a fact that one usually exits doubt without realizing it.” He warns us further: “We are dogma-prone from our mother’s wombs.”

There’s a fascinating real life story that Taleb gives here, and it illustrates the danger of making decisions in the real world on the basis of theoretical models that rule out the possibility of unknown extreme events. The context here is the financial world —which is purely Extremistan. And the theory used was the Modern Portfolio Theory — which is based on the gaussian distribution and therefore doesn’t work in Extremistan. On this Modern Portfolio Theory, Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger made some comments on the 1996 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting. Buffet said “it has no utility”, while Munger said “it involves a type of dementia”.

Here’s the story…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Robert Merton, Jr., and Myron Scholes were founding partners in the large speculative trading firm called Long-Term Capital Management, or LTCM. It was a collection of people with top-notch résumés, from the highest ranks of academia. They were considered geniuses. The ideas of portfolio theory inspired their risk management of possible outcomes—thanks to their sophisticated “calculations.” They managed to enlarge the ludic fallacy to industrial proportions.

Then, during the summer of 1998, a combination of large events, triggered by a Russian financial crisis, took place that lay outside their models. It was a Black Swan. LTCM went bust and almost took down the entire financial system with it, as the exposures were massive. Since their models ruled out the possibility of large deviations, they allowed themselves to take a monstrous amount of risk. The ideas of Merton and Scholes, as well as those of Modern Portfolio Theory, were starting to go bust. The magnitude of the losses was spectacular, too spectacular to allow us to ignore the intellectual comedy. Many friends and I thought that the portfolio theorists would suffer the fate of tobacco companies: they were endangering people’s savings and would soon be brought to account for the consequences of their Gaussian-inspired methods.

None of that happened. Instead, MBAs in business schools went on learning portfolio theory.

In contrast to these people who fall in the ludic fallacy, I find the perfect counter-example in some of the greatest scientists and creators — who highlight the importance of being humble about what we know and always remain skeptical.

Here’s Isaac Newton: “To myself I am only a child playing on the beach, while vast oceans of truth lie undiscovered before me.”

And Richard Feynman: “I was born not knowing and have had only a little time to change that here and there.”

Here’s Niels Bohr: “Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation, but as a question.”

And Elon Musk has said: “You should take the approach that you’re wrong. Your goal is to be less wrong.”

The key here is that they are all aware that they always lack knowledge, and therefore they are aware that they can’t compute all the risks. So this mindset spares them from falling in the ludic fallacy — where people think they can compute all the risks as if it was a game in the casino.

💡Idea #15: Epistemic Arrogance & Epistemic Humility

This mindset of being aware that you lack knowledge is also known as Epistemic Humility, and it’s useful to fight what Taleb calls Epistemic Arrogance.

The Epistemic Arrogance happens when our increase in knowledge comes with an even greater increase in confidence, which make our increase in knowledge at the same time an increase in confusion, ignorance, and conceit.

Taleb writes that this epistemic arrogance bears a double effect: We overestimate what we know, and underestimate uncertainty, by compressing the range of possible uncertain states (i.e., by reducing the space of the unknown).

As we’ve seen, the opposite of epistemic arrogance is epistemic humility. And with regards to epistemic humility, Taleb says the following…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Someone with a low degree of epistemic arrogance is not too visible, like a shy person at a cocktail party. We are not predisposed to respect humble people, those who try to suspend judgment. Now contemplate epistemic humility. Think of someone heavily introspective, tortured by the awareness of his own ignorance. He lacks the courage of the idiot, yet has the rare guts to say “I don’t know.” He does not mind looking like a fool. He hesitates, he will not commit, and he agonizes over the consequences of being wrong. He introspects, introspects, and introspects until he reaches physical and nervous exhaustion.

This does not necessarily mean that he lacks confidence, only that he holds his own knowledge to be suspect.

And then Taleb goes on to say that his dream society is one in which anyone of rank is full of epistemic humility rather than epistemic arrogance.

And when he says that a person with epistemic humility “does not mind looking like a fool” I couldn’t help but recall a quote from the renowned psychiatrist Carl Jung where he said “the fool is the precursor to the savior.” And Fyodor Dostoevsky also said “The cleverest of all, in my opinion, is the man who calls himself a fool at least once a month.” And I think the lesson here is that a person who genuinely wants to learn and understand things and doesn’t care about looking smart, will become very smart in the long run.

💡Idea #16: The Fire Hydrant Experiment

This is a fascinating experiment that shows the difficulty in changing our ideas and beliefs, and how sometimes more information leads to worse understanding.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Show two groups of people a blurry image of a fire hydrant, blurry enough for them not to recognize what it is. For one group, increase the resolution slowly, in ten steps. For the second, do it faster, in five steps. Stop at a point where both groups have been presented an identical image and ask each of them to identify what they see. The members of the group that saw fewer intermediate steps are likely to recognize the hydrant much faster. Moral? The more information you give someone, the more hypotheses they will formulate along the way, and the worse off they will be. They see more random noise and mistake it for information.

The problem is that our ideas are sticky: once we produce a theory, we are not likely to change our minds—so those who delay developing their theories are better off. When you develop your opinions on the basis of weak evidence, you will have difficulty interpreting subsequent information that contradicts these opinions, even if this new information is obviously more accurate. Two mechanisms are at play here: the confirmation bias that we saw earlier, and belief perseverance, the tendency not to reverse opinions you already have. Remember that we treat ideas like possessions, and it will be hard for us to part with them.

The author Robert Greene also offers a great insight on this tendency of belief perseverance…

🟠 Robert Greene:

Science claims a search for truth that would seem to protect it from conservatism and the irrationality of habit: It is a culture of innovation. Yet when Charles Darwin published his ideas of evolution, he faced fiercer opposition from his fellow scientists than from religious authorities. His theories challenged too many fixed ideas. Jonas Salk ran into the same wall with his radical innovations in immunology, as did Max Planck with his revolutionizing of physics. Planck later wrote of the scientific opposition he faced, “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

👉 Book: The 48 Laws of Power

This idea also relates to what Charlie Munger called the Inconsistency-avoidance tendency, which has a big influence in the formation of habits…

🟠 Charlie Munger:

The brain of man conserves programming space by being reluctant to change, which is a form of inconsistency avoidance. We see this in all human habits, constructive and destructive. Few people can list a lot of bad habits that they have eliminated, and some people cannot identify even one of these. Instead, practically everyone has a great many bad habits he has long maintained despite their being known as bad.

Given this situation, it is not too much in many cases to appraise early-formed habits as destiny. When Marley’s miserable ghost [in A Christmas Carol] says, “I wear the chains I forged in life,” he is talking about the chains of habit that were too light to be felt before they became too strong to be broken.

The rare life that is wisely lived has in it many good habits maintained and many bad habits avoided or cured. The great rule that helps here is again from Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” What Franklin is here indicating, in part, is that inconsistency-avoidance tendency makes it much easier to prevent a habit than to change it.

👉 Book: Poor Charlie’s Almanack

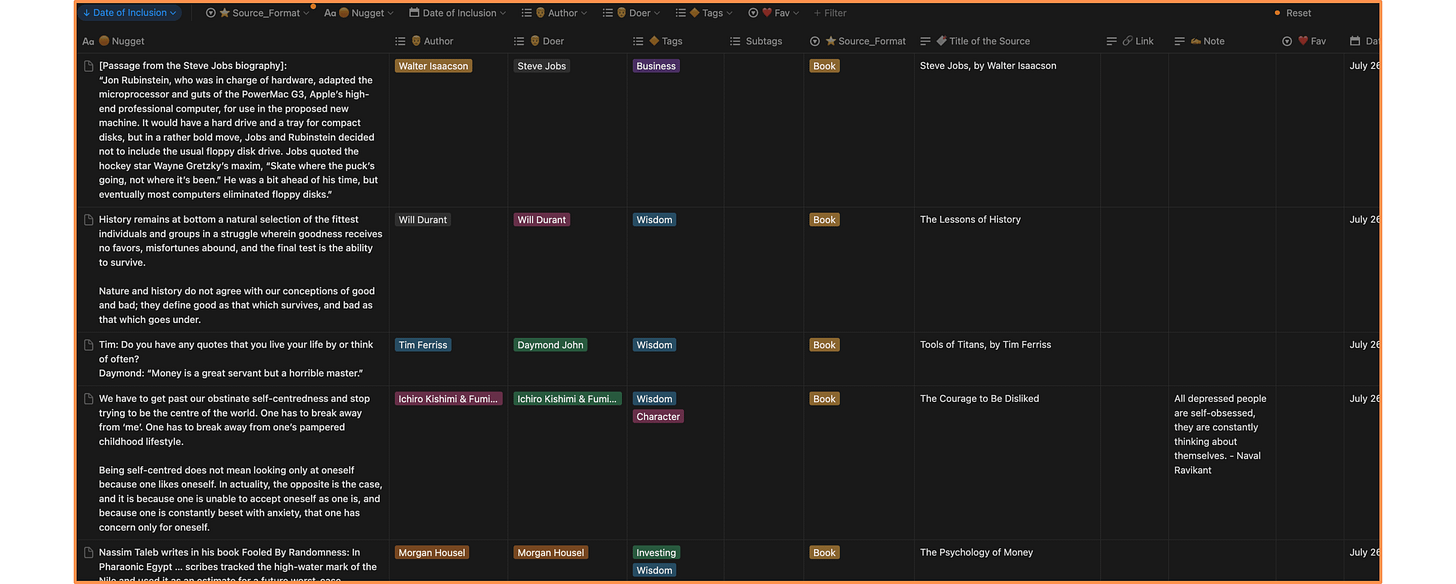

All the nuggets I’ve picked for the past 5 years are saved and classified in a searchable database, which (as of December 2025) contains 5,051 timeless ideas (sourced directly from the most influential doers and entrepreneurs — captured on books, interviews/podcasts, tweets, and articles).

I call this database Doers Notebook.

🤔 Why did I build this?

Well, as the Latin motto goes, “A chief part of learning is simply knowing where you can find a thing.” And since it’s all 🔎 searchable, we only need to type a keyword to immediately get a list of insights related to it!

For instance, if I’m unsure about how to get more sales in my business, I can simply type the word “sales” and immediately get 126 insights relevant to sales! In this case from Jim Edwards, Peter Thiel, Naval Ravikant, Paul Graham, Sam Altman, Balaji Srinivasan, Nassim Taleb, and many other remarkable individuals.

It’s like having a second brain 🧠 from which we can pull wisdom on demand, to help us significantly decrease the error rate in our judgment and also get new perspectives on how to solve problems.

In an age of infinite leverage [code and media], judgment is the most important skill.

- Naval Ravikant

A change of perspective is worth 80 IQ points.

- Alan Kay

If you want to see Doers Notebook in action, I made a screen record!

You can also go directly to DoersNotebook.com

💡Idea #17: Budget for Uncertainty

On making plans and projections, Nassim Taleb argues that we systematically underestimate their duration and cost. And this happens because we never give space for the unknown unknowns, we only plan based on what we can see and think of. And uncertainty, the unknown unkonwns, almost always have a one-side effect on planning and projecting — which is a negative one, that either delays or makes the project more expensive. Just think of a house renovator making a projection, it almost always will end up taking longer and costing more than the initial projection.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

There’s the nerd effect, which stems from the mental elimination of off-model risks, or focusing on what you know. You view the world from within a model. Consider that most delays and cost overruns arise from unexpected elements that did not enter into the plan—that is, they lay outside the model at hand—such as strikes, electricity shortages, accidents, bad weather, or rumors of Martian invasions. These small Black Swans that threaten to hamper our projects do not seem to be taken into account. They are too abstract—we don’t know how they look and cannot talk about them intelligently.

We cannot truly plan, because we do not understand the future—but this is not necessarily bad news. We could plan while bearing in mind such limitations. It just takes guts.

It is often said that “is wise he who can see things coming.” Perhaps the wise one is the one who knows that he cannot see things far away.

💡Idea #18: Ditch the 5-year Plan

Taleb tells a personal story of when he worked at a European-owned financial institution back in 1998. He tells how every summer the 5 managers of the trading unit were supposed to meet in order to formulate the 5 year plan…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

A five-year plan? To a fellow deeply skeptical of the central planner, the notion was ludicrous; growth within the firm had been organic and unpredictable, bottom-up not top-down. It was well known that the firm’s most lucrative department was the product of a chance call from a customer asking for a specific but strange financial transaction. The firm accidentally realized that they could build a unit just to handle these transactions, since they were profitable, and it rapidly grew to dominate their activities.

The managers flew across the world in order to meet and sat down to brainstorm during these meetings, about, of course, the medium-term future—they wanted to have “vision.” But then an event occurred that was not in the previous five-year plan: the Black Swan of the Russian financial default of 1998 and the accompanying meltdown of the values of Latin American debt markets. It had such an effect on the firm that, although the institution had a sticky employment policy of retaining managers, none of the five was still employed there a month after the sketch of the 1998 five-year plan. Yet I am confident that today their replacements are still meeting to work on the next “five-year plan.” We never learn.

This story from Nassim reminded me of an interview I watched of the founder of Nvidia Jensen Huang, where he said that the long-term plan of Nvidia is: What are we doing today?

🟠 Jensen Huang:

Very few people know this, but I don’t wear a watch. And the reason why I don’t wear watches is: Now is the most important time. You’ll be surprised—I’m not at all ambitious. I don’t aspire to do more; I aspire to do better at what I’m currently doing. I’m not reaching for more. I wait for the world to come to me. People who know me also knows [that] NVIDIA doesn’t have a long-term strategy. We have no long-term plan. Our definition of a long-term plan is: What are we doing today?

(Source: Tweet by Arjun Khemani)

Charlie Munger has also talked about the dangers of planning…

🟠 Charlie Munger:

At Berkshire there has never been a master plan. Anyone who wanted to do it, we fired because it takes on a life of its own and doesn’t cover new reality. We want people taking into account new information.

(Source: Farnam Street)

💡Idea #19: Maximize the Serendipity Around You

Taleb argues that the process of innovation is almost entirely driven by trial and error and lucky accidents.

In the same way, he says that in life one should be exposed to the possibility of positive accidents. To maximize the serendipity around you, so that you have the chance to get lucky. But many people don’t do this because they are afraid of failure, even when these failures are not consequential…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

We have psychological and intellectual difficulties with trial and error, and with accepting that series of small failures are necessary in life. My colleague Mark Spitznagel understood that we humans have a mental hang-up about failures: “You need to love to lose” was his motto. In fact, the reason I felt immediately at home in America is precisely because American culture encourages the process of failure, unlike the cultures of Europe and Asia where failure is met with stigma and embarrassment. America’s specialty is to take these small risks for the rest of the world, which explains this country’s disproportionate share in innovations. Once established, an idea or a product is later “perfected” over there.

And just to add another perspective, I always loved this line by Peter Thiel…

🟠 Peter Thiel:

There’s always the risk of doing something that’s not that significant or meaningful. You could say a track in Law School is a low-risk track from one perspective. [But] it may still be a very high-risk track in the sense that maybe you have a high-risk of not doing something meaningful with your life.

(Source: Some Career Advice by Peter Thiel - Stanford Campus)

💡Idea #20: Look for Asymmetric Outcomes

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Put yourself in situations where favorable consequences are much larger than unfavorable ones.

Indeed, the notion of asymmetric outcomes is the central idea of this book: I will never get to know the unknown since, by definition, it is unknown. However, I can always guess how it might affect me, and I should base my decisions around that.

This idea is often erroneously called Pascal’s wager, after the philosopher and (thinking) mathematician Blaise Pascal. He presented it something like this: I do not know whether God exists, but I know that I have nothing to gain from being an atheist if he does not exist, whereas I have plenty to lose if he does. Hence, this justifies my belief in God.

This idea that in order to make a decision you need to focus on the consequences (which you can know) rather than the probability (which you can’t know) is the central idea of uncertainty. Much of my life is based on it.

One of my favorite stories on looking for positive asymmetries is a story from Richard Branson when he was starting his airline Virgin. Most people would think that he took a lot of risk when he started the airline, but he actually took a very limited risk. Because he went to Boeing and negotiated a deal where they could send the planes back if it didn’t work out and he wasn’t liable.

So I like this example because it’s not just about someone looking for asymmetries, it’s someone who is obsessed with asymmetries. His first question to every business is, “What’s the downside and how do I protect it?”

💡Idea #21: Set up your own Game

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

I once received another piece of life-changing advice, which I find applicable, wise, and empirically valid. My classmate in Paris, the novelist-to-be Jean-Olivier Tedesco, pronounced, as he prevented me from running to catch a subway, “I don’t run for trains.”

Snub your destiny. I have taught myself to resist running to keep on schedule. This may seem a very small piece of advice, but it registered. In refusing to run to catch trains, I have felt the true value of elegance and aesthetics in behavior, a sense of being in control of my time, my schedule, and my life. Missing a train is only painful if you run after it! Likewise, not matching the idea of success others expect from you is only painful if that’s what you are seeking.

You stand above the rat race and the pecking order, not outside of it, if you do so by choice.

Quitting a high-paying position, if it is your decision, will seem a better payoff than the utility of the money involved (this may seem crazy, but I’ve tried it and it works). This is the first step toward the stoic’s throwing a four-letter word at fate. You have far more control over your life if you decide on your criterion by yourself.

Mother Nature has given us some defense mechanisms: as in Aesop’s fable, one of these is our ability to consider that the grapes we cannot (or did not) reach are sour. But an aggressively stoic prior disdain and rejection of the grapes is even more rewarding. Be aggressive; be the one to resign, if you have the guts.

It is more difficult to be a loser in a game you set up yourself.

In Black Swan terms, this means that you are exposed to the improbable only if you let it control you. You always control what you do; so make this your end.

Going back to this line where Taleb says “You have far more control over your life if you decide on your criterion by yourself”, it reminded me of something I learned from Peter Thiel.

Thiel says that one of the reasons for why we tend to blindly follow other people’s criterion, instead of our own criterion, is that humans feel safety in the crowds. We feel validated when we pursue things that other people are pursuing too.

🟠 Peter Thiel:

There’s something where we find competition strangely reassuring. We find it validating, when you compete for things where there are lots of people doing it. And there’s sort of this perception of safety in crowds — if a lot of people are trying to get something, it must be valuable. Whereas if nobody’s trying to do something, that’s already really uncomfortable. And I think the word “ape” already in the time of Shakespeare meant both primate and to imitate. And there is this rather disturbing aspect of human nature where people are ape like, sheep like, lemming like, unbelievably herd like, and we’re sort of attracted to doing things that other people do. We’re attracted to compete for all these things. And compete the most intensely for things that often matter the least.

(Source: London School of Economics)

I hope you enjoyed today’s letter!

I highly recommend buying The Black Swan. And if you buy it using this link, you’ll be supporting the blog (and podcast) at no extra cost to you.

Talk you soon,

Your nuggets friend Julio :)

Thank you!

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb -key takeaways !! https://substack.com/@deerajrp/note/c-186341067?r=4qb27v