Skin In The Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb: 16 Key Ideas & Highlights

👋 Hey friend,

In this blog post, I share the 16 key ideas — with direct quotes from the book — I picked from reading Skin In The Game, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Skin In The Game was an amazing read! And it’s full of timeless and practical insights that root back to the ancient wisdom of the greeks and the romans (Taleb illustrates his ideas with many of these mythical ancient stories and accounts from ancient kings and philosophers) — so the information is time-tested and very, very entertaining!

By the way, I also made it into a 🎧 podcast episode (with a manually written transcription on-screen). So if you prefer to listen, open any of the links below to listen on your favorite podcast app…

YouTube (with perfect transcription on-screen):

Spotify (with perfect transcription on-screen):

Apple Podcasts:

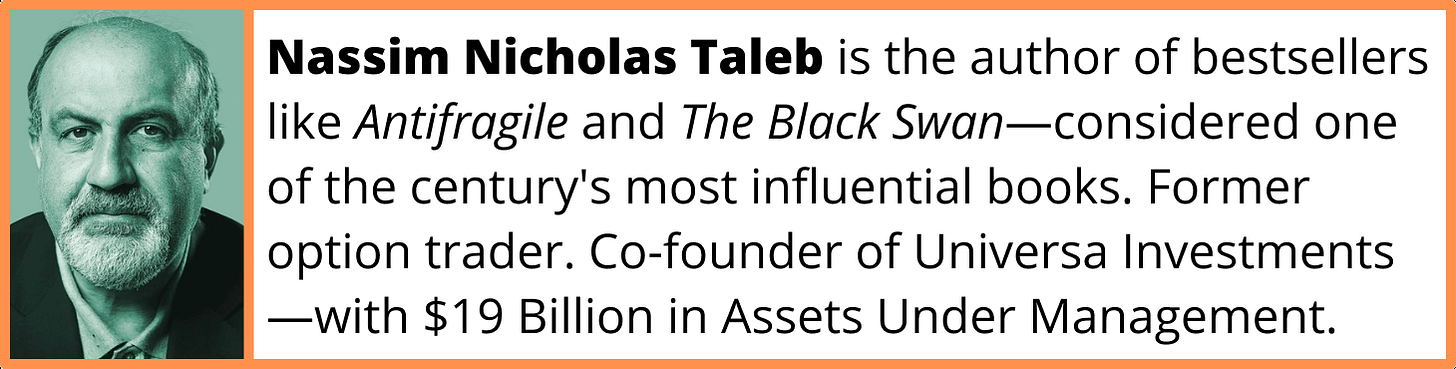

👤 Nassim Nicholas Taleb

💡Idea #1: Never Lose Touch with Reality

The first idea is Never Lose Touch with Reality. This means you need to have skin in the game on everything that you do. As we will see, this has both an epistemological dimension and an ethical dimension. We will explore this ethical dimension a bit later, first let’s get into the epistemological one — which is the creation of knowledge.

Taleb argues that having skin in the game is necessary to generate knowledge, create inventions, and drive progress. And he illustrates this with the story of the mythical Antaeus:

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Antaeus was a giant, or rather a semi-giant of sorts, the literal son of Mother Earth, Gaea, and Poseidon, the god of the sea. He had a strange occupation, which consisted of forcing passersby in his country, (Greek) Libya, to wrestle; his thing was to pin his victims to the ground and crush them. This macabre hobby was apparently the expression of filial devotion; Antaeus aimed at building a temple to his father, Poseidon, using for raw material the skulls of his victims.

Antaeus was deemed to be invincible, but there was a trick. He derived his strength from contact with his mother, Earth. Physically separated from contact with Earth, he lost all his powers. Hercules, as part of his twelve labors (in one variation of the tale), had for homework to whack Antaeus. He managed to lift him off the ground and terminated him by crushing him as his feet remained out of contact with his mamma.

We retain from this first vignette that, just like Antaeus, you cannot separate knowledge from contact with the ground. Actually, you cannot separate anything from contact with the ground. And the contact with the real world is done via skin in the game—having an exposure to the real world, and paying a price for its consequences, good or bad. The abrasions of your skin guide your learning and discovery, a mechanism of organic signaling, what the Greeks called pathemata mathemata (“guide your learning through pain,” something mothers of young children know rather well). I have shown in Antifragile that most things that we believe were “invented” by universities were actually discovered by tinkering and later legitimized by some type of formalization. The knowledge we get by tinkering, via trial and error, experience, and the workings of time, in other words, contact with the earth, is vastly superior to that obtained through reasoning, something self-serving institutions have been very busy hiding from us.

So we need a feedback loop with reality if we want to improve at anything. Naval Ravikant said that the gold standard for feedback loops are nature, physics, and free markets. And the worse way to get feedback is anything that is social — such as friends, academic peers, or peers in a big firm.

The reason is that nature, physics, and free markets will give you the absolute truth, and you need the truth — no matter how harsh it is — in order to make progress.

On the other hand, friends and peers have an incentive to hide the truth, either because they don’t wanna hurt your feelings or maybe because they have some feelings of envy towards you. But nature, physics and free markets don’t have any feelings about you, so they will show you the truth. As Richard Feynman said: “Imagine how much harder physics would be if electrons had feelings.” And in the case of free markets, you get the truth on whether your product is good or not by looking at how much is selling and what the customers are saying about your product.

And this connection between skin in the game and knowledge has another aspect. Which is that it can make boring things less boring, and even interesting and fun.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Skin in the game can make boring things less boring. When you have skin in the game, dull things like checking the safety of the aircraft because you may be forced to be a passenger in it cease to be boring. If you are an investor in a company, doing ultra-boring things like reading the footnotes of a financial statement (where the real information is to be found) becomes, well, almost not boring.

But there is an even more vital dimension. Many addicts who normally have a dull intellect and the mental nimbleness of a cauliflower—or a foreign policy expert—are capable of the most ingenious tricks to procure their drugs. When they undergo rehab, they are often told that should they spend half the mental energy trying to make money as they did procuring drugs, they are guaranteed to become millionaires. But, to no avail. Without the addiction, their miraculous powers go away. It was like a magical potion that gave remarkable powers to those seeking it, but not those drinking it.

A confession. When I don’t have skin in the game, I am usually dumb. My knowledge of technical matters, such as risk and probability, did not initially come from books. It did not come from lofty philosophizing and scientific hunger. It did not even come from curiosity. It came from the thrills and hormonal flush one gets while taking risks in the markets. I never thought mathematics was something interesting to me until, when I was at Wharton, a friend told me about financial options and complex derivatives.

I immediately decided to make a career in them. It was a combination of financial trading and complicated probability. The field was new and uncharted. I knew in my guts there were mistakes in the theories that used the conventional bell curve and ignored the impact of extreme events. I knew in my guts that academics had not the slightest clue about the risks. So, to find errors in the estimation of these probabilistic securities, I had to study probability, which mysteriously and instantly became fun, even gripping. When there was risk on the line, suddenly a second brain in me manifested itself, and the probabilities of intricate sequences became suddenly effortless to analyze and map.

When there is fire, you will run faster than in any competition. When you ski downhill some movements become effortless.

…

Many kids would learn to love mathematics if they had some investment in it, and, more crucially, they would build an instinct to spot its misapplications.

Now, a personal experience related to this idea:

I found interesting subjects during my Chemical Engineering degree. But it wasn’t until I read a book about investing and started buying stocks that a compulsive need for learning about investing and business took hold on me. That made me go for a Master’s degree in Business Management, and I confess that I’ve never — in my whole life — being so deep into my studies. I devoured all the material, I would raise my hand on every class and ask challenging questions to the teachers, and for the first time I would naturally excel at the subjects.

Now, I want to clarify that, in hindsight, I don’t think the Master’s degree was very useful for learning about investing or learning how to start a business. It was more focused on how to become a manager employee at a mid or large size business — also with academic models for finance and economics that don’t work in real life.

Similar to this idea, just having a vision for a real-world project that you care about can make learning much more interesting. Robert Pirsig, the author of the bestseller book The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, gives the example of two students in a class of Mechanical Engineering. The first student has a genuine interest in machines and also some experience as a mechanic. The other student is just concerned about his grades. Who do you think is gonna find the lessons more interesting? Obviously the first student, because he sees his learning as a means to get better at something that he deeply cares about, and can also see all the practical implications of the things he is studying. This same principle was applied at the experimental school that Elon Musk funded for his children and SpaceX employees, where learning happened as a byproduct of working on ambitious real-world projects.

Now let’s get into the ethical dimension of skin in the game.

💡Idea #2: Skin In The Game Is About Honor

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Finally and centrally, skin in the game is about honor as an existential commitment, and risk taking (a certain class of risks) as a separation between man and machine and (some may hate it) a ranking of humans.

If you do not take risks for your opinion, you are nothing.

And I will keep mentioning that I have no other definition of success than leading an honorable life. We intimated that it is dishonorable to let others die in your stead.

Honor implies that there are some actions you would categorically never do, regardless of the material rewards. She accepts no Faustian bargain, would not sell her body for $500; it also means she wouldn’t do it for a million, nor a billion, nor a trillion. And it is not just a via negativa stance, honor means that there are things you would do unconditionally, regardless of the consequences. Consider duels, which have robbed us of the great Russian poet Pushkin, the French mathematician Galois, and, of course, many more, at a young age: people incurred a significant probability of death just to save face. Living as a coward was simply no option, and death was vastly preferable, even if, as in the case of Galois, one invented a new and momentous branch of mathematics while still a teenager. As a Spartan mother tells her departing son: “With it or on it,” meaning either return with your shield or don’t come back alive (the custom was to carry the dead body flat on it); only cowards throw away their shields to run faster.

If you want to consider how modernity has destroyed some of the foundations of human values, contrast the above unconditionals with modernistic accommodations: people who, say, work for disgusting lobbies (representing the interests of, say, Saudi Arabia in Washington) or knowingly play the usual unethical academic game, come to grips with their condition by producing arguments such as “I have children to put through college.” People who are not morally independent tend to fit ethics to their profession, rather than find a profession that fits their ethics.

This last line from Taleb reminded me a great quote from George Santayana: “A man is morally free when he judges the world, and judges other men, with uncompromising sincerity.”

Now back to the passage…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

There is another dimension of honor: engaging in actions going beyond mere skin in the game to put oneself at risk for others, have your skin in other people’s game; sacrifice something significant for the sake of the collective.

I think the writer Ernest Hemingway captured this perfectly…

🟠 Ernest Hemingway:

The best people possess a feeling for beauty, the courage to take risks, the discipline to tell the truth, the capacity for sacrifice. Ironically, their virtues make them vulnerable; they are often wounded, sometimes destroyed.

But as I think Taleb would argue, is better to be destroyed than to live without honor.

💡Idea #3: Soul In The Game

A great example of individuals with soul in the game is the artisans…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Artisans do things for existential reasons first, financial and commercial ones later. Their decision making is never fully financial, but it remains financial.

Secondly, they have some type of “art” in their profession; they stay away from most aspects of industrialization; they combine art and business. And third, they put some soul in their work: they would not sell something defective or even of compromised quality because it hurts their pride. Finally, they have sacred taboos, things they would not do even if it markedly increased profitability.

This idea of the artisans being unconditional on their willingness to not compromise on the quality of their products reminded me what David Senra calls “The Anti-business billionaires.” He mentions James Dyson, Steve Jobs, and Yvon Chouinard as perfect examples, as they have always been obsessed with the quality of their products and they would never compromise on that to increase short-term profitability. And the ironic thing is that, in the long-run, they end up with the money anyways because they build insanely great products. That greatness is eventually transmitted to customers — who then become loyal recurrent buyers of these brands.

In the case of Steve Jobs, this was an early lesson that he got from his adoptive father. Walter Isaacson talks about it on the Steve Jobs biography:

🟠 Walter Isaacson:

The childhood that Paul and Clara Jobs created for their new son was, in many ways, a stereotype of the late 1950s. When Steve was two they adopted a girl they named Patty, and three years later they moved to a tract house in the suburbs. The finance company where Paul worked as a repo man, CIT, had transferred him down to its Palo Alto office, but he could not afford to live there, so they landed in a subdivision in Mountain View, a less expensive town just to the south.

There Paul tried to pass along his love of mechanics and cars. “Steve, this is your workbench now,” he said as he marked off a section of the table in their garage. Jobs remembered being impressed by his father’s focus on craftsmanship. “I thought my dad’s sense of design was pretty good,” he said, “because he knew how to build anything. If we needed a cabinet, he would build it. When he built our fence, he gave me a hammer so I could work with him.”

Fifty years later the fence still surrounds the back and side yards of the house in Mountain View. As Jobs showed it off to me, he caressed the stockade panels and recalled a lesson that his father implanted deeply in him. It was important, his father said, to craft the backs of cabinets and fences properly, even though they were hidden. “He loved doing things right. He even cared about the look of the parts you couldn’t see.”

👉 Book: Steve Jobs, by Walter Isaacson.

I’m also reminded of a beautiful quote from Steve Jobs where he says that when you build something truly great — without cutting corners — that is a form of appreciation to other people.

🟠 Steve Jobs:

There’s lots of ways to be, as a person. And some people express their deep appreciation in different ways. But one of the ways that I believe people express their appreciation to the rest of humanity is to make something wonderful and put it out there. And you never meet the people. You never shake their hands. You never hear their story or tell yours. But somehow, in the act of making something with a great deal of care and love, something’s transmitted there. And it’s a way of expressing to the rest of our species our deep appreciation. So we need to be true to who we are and remember what’s really important to us.

👉 Book: Make Something Wonderful, by Steve Jobs.

Another great reference to this idea of working with soul in the game comes from Leonardo da Vinci when he painted the portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci…

🟠 Paul Graham:

This sounds like a paradox, but a great painting has to be better than it has to be. For example, when Leonardo painted the portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci in the National Gallery, he put a juniper bush behind her head. In it he carefully painted each individual leaf. Many painters might have thought, this is just something to put in the background to frame her head. No one will look that closely at it. Not Leonardo. How hard he worked on a part of a painting didn’t depend at all on how closely he expected anyone to look at it. He was like Michael Jordan. Relentless.

Relentlessness wins because, in the aggregate, unseen details become visible. When people walk by the portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, their attention is often immediately arrested by it, even before they look at the label and notice that it says Leonardo da Vinci. All those unseen details combine to produce something that’s just stunning, like a thousand barely audible voices all singing in tune.

👉 Book: Hackers and Painters, by Paul Graham.

💡Idea #4: Heroes Were Not Library Rats

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

If you want to study classical values such as courage or learn about stoicism, don’t necessarily look for classicists. One is never a career academic without a reason. Read the texts themselves: Seneca, Caesar, or Marcus Aurelius, when possible. Or read commentators on the classics who were doers themselves, such as Montaigne—people who at some point had some skin in the game, then retired to write books. Avoid the intermediary, when possible. Or forget about the texts, just engage in acts of courage.

For studying courage in textbooks doesn’t make you any more courageous than eating cow meat makes you bovine.

By some mysterious mental mechanism, people fail to realize that the principal thing you can learn from a professor is how to be a professor—and the chief thing you can learn from, say, a life coach or inspirational speaker is how to become a life coach or inspirational speaker. So remember that the heroes of history were not classicists and library rats, those people who live vicariously in their texts. They were people of deeds and had to be endowed with the spirit of risk taking. To get into their psyches, you will need someone other than a career professor teaching stoicism. They almost always don’t get it (actually, they never get it). In my experience, from a series of personal fights, many of these “classicists,” who know in intimate detail what people of courage such as Alexander, Cleopatra, Caesar, Hannibal, Julian, Leonidas, Zenobia ate for breakfast, can’t produce a shade of intellectual valor. Is it that academia (and journalism) is fundamentally the refuge of the stochastophobe tawker? That is, the voyeur who wants to watch but not take risks? It appears so.

So the big difference between the doer and the academic thinker is that the doer has skin in the game. And Steve Jobs argues that over time, it is the doer that becomes the major thinker, because he accumulates a type of knowledge that is much more robust and practical than the theoretical knowledge of the academic thinker — which is much more fragile and less useful…

🟠 Steve Jobs:

It is very easy to take credit for the thinking. The doing is more concrete. And when you dig a little deeper usually you find that the people who did it were also the people who worked through the hard intellectual problems as well.

…

The doers are the major thinkers.

A great example in the (mostly theoretical) world of philosophy, is the philosopher of the early 20th century Simone Weil — who had the opportunity to just write and produce philosophy from the comfort of a desk. But she was more compelled to act rather than just theorize. So she actually lived her philosophy and stood up for her ideas. Taleb also mentioned Simone Weil in the book, he called her a secular saint and wrote: “While coming from the French Jewish upper class, [Simone Weil] spent a year in a car factory so the working class could be something other than an abstract construct for her.”

Here’s a great line from Elon Musk to remind ourselves to have a bias to action:

🟠 Elon Musk:

You could either be a spectator or a participant. And so, I guess I’d rather be a participant than a spectator.

👉 Source: Elon Musk on YC

I’m actually fascinated by the wisdom of the doers and I’ve spent the last 5 years capturing their insights in their own words. This is all saved and classified in a searchable database which currently contains over 5,000 timeless ideas.

I call this database Doers Notebook.

So if I’m unsure about how to get more sales in my business, I can simply type the word “sales” and immediately get 126 insights relevant to sales! In this case from Jim Edwards, Peter Thiel, Naval Ravikant, and many other remarkable individuals.

It’s like having a second brain 🧠 from which we can pull wisdom on demand, to help us significantly decrease the error rate in our judgment and also get new perspectives on how to solve problems.

“In an age of infinite leverage [through code and media], judgment is the most important skill.” - Naval Ravikant

“A change of perspective is worth 80 IQ points.” - Alan Kay

Plus, it also comes with an app that looks just like X, but the posts are insights from the database — which are reshuffled every 15 minutes so that the feed is always fresh. That way, you can replace doomscrolling with micro-learning.

So if all this sounds interesting, just go to doersnotebook.com

💡Idea #5: The Public and The Private

The next idea is kind of the logical conclusion of the previous one. It’s about how living your ideas — in other words having skin in the game for what you believe in — is the moral thing to do. So what a person does in private should align with what he or she says in public. Taleb gives two examples to illustrate…

Example 1:

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

I was recently told that a famous Canadian socialist environmentalist, with whom I was part of a lecture series, abused waiters in restaurants, between lectures on equity, diversity, and fairness.

So here we have a mismatch between the public life of this person and his private life — resulting in a clear unethical behavior.

Example 2:

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Kids with rich parents talk about “class privilege” at privileged colleges such as Amherst—but in one instance, one of them could not answer Dinesh D’Souza’s simple and logical suggestion: Why don’t you go to the registrar’s office and give your privileged spot to the minority student next in line?

Clearly the defense given by people under such a situation is that they want others to do so as well—they require a systemic solution to every local perceived problem of injustice. I find that immoral. I know of no ethical system that allows you to let someone drown without helping him because other people are not helping, no system that says, “I will save people from drowning only if others too save other people from drowning.”

Which brings us to the principle:

[1] If your private life conflicts with your intellectual opinion, it cancels your intellectual ideas, not your private life.

[2] If your private actions do not generalize, then you cannot have general ideas.

💡Idea #6: Unpopular Virtue

The next idea, still on the dimension of morality, is that a true virtuous behavior must bear a personal cost. In other words, virtue is inseparable from risk-taking and sacrifice.

So if you do or say something good which is also popular and well seen by others, then you cannot tell if it’s a genuine virtuous act — because you could be doing it to elevate your status, be liked by others, or get some kind of reward. Whereas if you do or say something good which is unpopular in your social circle, then you can say that’s a virtuous act — because it came at a personal cost to you.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Sticking up for truth when it is unpopular is far more of a virtue, because it costs you something—your reputation. If you are a journalist and act in a way that risks ostracism, you are virtuous. Some people only express their opinions as part of mob shaming, when it is safe to do so, and, in the bargain, think that they are displaying virtue. This is not virtue but vice, a mixture of bullying and cowardice.

And of course this personal cost can take other forms. For instance in the context of religion, Taleb gives this example…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

In the Eastern Mediterranean pagan world (Greco-Semitic), no worship was done without sacrifice. The gods did not accept cheap talk. It was all about revealed preferences. Also, burnt offerings were precisely burnt so no human would consume them. Actually, not quite: the high priest got his share; priesthood was quite a lucrative position since in the pre-Christian, Greek-speaking Eastern Mediterranean, the offices of high priests were often auctioned off.

…

Love without sacrifice is theft. This applies to any form of love, particularly the love of God.

Finally, Taleb says that courage (risk taking) is the highest virtue, and it’s the only one you cannot fake.

And when Taleb talks about courage he is not referring to selfish courage — like the kind displayed by a gambler. The courage he talks about is never a selfish action: Courage is when you sacrifice your own well-being for the sake of the survival of a layer higher than yours. And this layer — he says —can be family, friends, humanity, and even the preservation of the planet. This connects to the concept of self-transcendence proposed by Viktor Frankl…

🟠 Viktor Frankl:

By declaring that man is responsible and must actualize the potential meaning of his life, I wish to stress that the true meaning of life is to be discovered in the world rather than within man or his own psyche, as though it were a closed system. I have termed this constitutive characteristic “the self-transcendence of human existence.” It denotes the fact that being human always points, and is directed, to something, or someone, other than oneself—be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself. What is called self-actualization is not an attainable aim at all, for the simple reason that the more one would strive for it, the more he would miss it. In other words, self-actualization is possible only as a side-effect of self-transcendence.

👉 Book: Man’s Search for Meaning, by Viktor Frankl.

I found another perspective on the book The Courage To Be Disliked…

🟠 Ichiro Kishimi & Fumitake Koga:

PHILOSOPHER: … So, the issue that arises at this point is, how on earth can one become able to feel one has worth?

YOUTH: Yes, that’s it exactly! I need you to explain that very clearly, please.

PHILOSOPHER: It’s quite simple. It is when one is able to feel I am beneficial to the community that one can have a true sense of one’s worth. This is the answer that would be offered in Adlerian psychology.

YOUTH: That I am beneficial to the community?

PHILOSOPHER: That one can act on the community; that is to say, on other people, and that one can feel I am of use to someone. Instead of feeling judged by another person as ‘good’, being able to feel, by way of one’s own subjective viewpoint, that I can make contributions to other people. It is at that point that, at last, we can have a true sense of our own worth.

👉 Book: The Courage To Be Disliked, by Ichiro Kishimi & Fumitake Koga.

💡Idea #7: Beware of Advice that Benefits the Advice-giver (And Never Harms Him)

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

I have learned a lesson from my own naive experiences:

Beware of the person who gives advice, telling you that a certain action on your part is “good for you” while it is also good for him, while the harm to you doesn’t directly affect him.

Of course such advice is usually unsolicited. The asymmetry is when said advice applies to you but not to him—he may be selling you something, or trying to get you to marry his daughter or hire his son-in-law.

…

Indeed, in the dozen or so cases I can pull from memory, it always turns out that what is presented as good for you is not really good for you but certainly good for the other party.

After reading this passage from Taleb I recalled how many times I go to the bank I get unsolicited advice from a bank employee on how I should invest in one of their funds. And then he proceeds to show me charts of how well these funds have performed in the past and how much money I could make. And if it wasn’t because I had already learned a lot from Charlie Munger and other remarkable investors, I might have fallen under the impression that this bank employee actually wanted to help me — but that couldn’t be further from the truth.

The truth is that banks just cherry-pick their best-performing funds and show those to you, never mentioning the majority of their funds that performed badly. And of course if the bank starts 20 funds in year 1, they are sure to have a few funds that end up performing well — but this is due to chance rather than skill. Indeed, the survivorship bias is the secret weapon in the mutual fund industry.

🟠 Charlie Munger:

What they do in creating new funds is create 10 or 12 of them, and then pick one that happens to win, and then they show the historical record forever showing this big return. And of course the big return happens where they have practically no assets, and the return per dollar year in those investment funds is terrible, but it looks great when you look at it in an historical record. And it’s really fraudulent what they do. And what’s interesting about the modern culture, is that nobody in the mutual fund world seems to find that as crooked and detestable — but of course it is crooked.

👉 Source: Conversation between Charlie Munger and Steven Pinker

And on top of this problem they have a fee structure where they make money regardless of whether you make or lose money, so they have only upside in this business — they cannot lose. But the investor in the fund can definitely lose money.

So we can generalize this particular example to any situation where the advice-giver has something to gain, and no skin in the game — meaning that he won’t get harm if the advice ends up harming you.

💡Idea #8: Talking One’s Book & Revealed Preferences

Taleb argues that if you are going to give advice, you should have skin in the game on that advice. And if you are going to listen to someone else’s advice, make sure he or she has skin in the game on it. In other words, look at what people do, not what they say. Focus on actions, not words.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

I went on television once to announce a newly published book and got stuck in the studio, drafted to become part of a roundtable with two journalists plus the anchor. The topic of the day was Microsoft, a company that was in existence at the time. Everyone, including the anchor, chipped in. My turn came: “I own no Microsoft stock, I am short no Microsoft stock — meaning I would benefit from its decline, hence I can’t talk about it.”

I repeated my dictum of Prologue 1: Don’t tell me what you think, tell me what you have in your portfolio.

There was immeasurable confusion in the faces: a journalist is typically not supposed to talk about stocks he owns—and, what is worse, is supposed to always, always make pronouncements about stuff he can barely find on a map. A journalist is meant to be an impartial “judge”…

[But] in the absence of skin in the game, journalists will imitate, to be safe, the opinion of other journalists, thus creating monoculture and collective mirages.

Another problem stemming from this lack of skin in the game is that people will say things that are aligned with the idealized version of themselves — and how they want to be perceived by other people. So this can be very different from what they actually do, because what they do is an expression of who they actually are — rather than who they are trying to be. So one should never make the mistake of conflating stated preferences (what people say) with revealed preferences (what people do).

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The axiom of revelation of preferences (originating with Paul Samuelson, or possibly the Semitic gods), as you recall, states the following: you will not have an idea about what people really think, what predicts people’s actions, merely by asking them—they themselves don’t necessarily know. What matters, in the end, is what they pay for goods, not what they say they “think” about them, or the various possible reasons they give you or themselves for that. If you think about it, you will see that this is a reformulation of skin in the game. Even psychologists get it; in their experiments, their procedures require that actual dollars be spent for a test to be “scientific.” The subjects are given a monetary amount, and they watch how the subject formulates choices by examining how they spend the money.

My favorite illustration on this issue of stated preferences and revealed preferences comes from Gary Halbert — who is one of the greatest copywriters in history. In his book The Boron Letters (which is a collection of letters that he wrote to his son Bond Halbert) he wrote:

🟠 Gary Halbert:

Here’s another little glimpse into one of the vagaries of human behavior: Once I asked at class at USC [University of Southern California] how many of them preferred to go to plays more than movies.

Lots of people raised their hands.

“Bull!” I said to them. “You are all fooling yourselves, and I’m going to prove it.” I then asked for a show of hands of those people who had seen a play in the last week or so.

No hands.

I then asked to see the hands of people who had seen a movie in the last week or so.

Many hands.

Bond, this phenomenon is common. All of us, including thee and me, have a slightly shrewd idea of ourselves. We often try to convince others and ourselves that we are something we are not, something we have an idea we “should” be.

Therefore, truth, my good son, can be determined NOT by how people use their mouths, but rather, how they use their wallets.

I want to burn this message into your mind. Be skeptical of what people say. Be skeptical of surveys. Of questionnaires. Instead, believe in numbers. For example, if everybody you talk with says they like plays more than movies, and yet the numbers say that 10,000 times more people buy movie tickets, then you believe the numbers!

👉 Book: The Boron Letters, by Gary Halbert.

💡Idea #9: The Minority Rule

Now let’s move to one of the core ideas of the book — which is the Minority Rule.

When I first learned about this idea it blew my mind. It’s one of these things that once you see it, you can’t unsee it — and actually you start seeing it almost everywhere in the real world. Naval Ravikant also said in an interview with Nassim Taleb that this was one of his favorite ideas from Skin in the Game.

But before getting into the minority rule, we first need to understand complex systems…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The main idea behind complex systems is that the ensemble [or the group] behaves in ways not predicted by its components. The interactions matter more than the nature of the units. Studying individual ants will almost never give us a clear indication of how the ant colony operates. For that, one needs to understand an ant colony as an ant colony, no less, no more, not a collection of ants. This is called an “emergent” property of the whole, by which parts and whole differ because what matters are the interactions between such parts.

Taleb also gives the example of the entire field of neuroscience, where scientists are trying to understand how the brain works by just analyzing the individual neuron. They are not considering that a group of neurons is a completely different beast than the sum of the average neuron — because of all the trillions of interactions between the neurons. It is a complex system. And you can’t explain the behavior of a complex system by just looking at the behavior of the individual parts.

🟠 Robert Greene:

The great European charlatans of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries mastered the art of cultmaking. They lived, as we do now, in a time of transformation: Organized religion was on the wane, science on the rise. People were desperate to rally around a new cause or faith. The charlatans had begun by peddling health elixirs and alchemic shortcuts to wealth. Moving quickly from town to town, they originally focused on small groups—until, by accident, they stumbled on a truth of human nature: The larger the group they gathered around themselves, the easier it was to deceive.

The charlatan would station himself on a high wooden platform (hence the term “mountebank”) and crowds would swarm around him. In a group setting, people were more emotional, less able to reason. Had the charlatan spoken to them individually, they might have found him ridiculous, but lost in a crowd they got caught up in a communal mood of rapt attention. It became impossible for them to find the distance to be skeptical. Any deficiencies in the charlatan’s ideas were hidden by the zeal of the mass. Passion and enthusiasm swept through the crowd like a contagion, and they reacted violently to anyone who dared to spread a seed of doubt.

👉 Book: The 48 Laws of Power, by Robert Greene.

🟠 Mark Twain:

Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.

Now, let’s get into the Minority Rule.

Imagine a group of people, with all these interactions between them, and also imagine that there is a minority who believes in something or has a preference towards something, and a majority who believe in something different. The Minority Rule establishes that if this minority is intransigent (in other words: intolerant) — towards their belief or preference, and the majority don’t mind compromising, then the result is that the ideas or preferences of the minority will be imposed over the majority. So the majority will submit to the minority (Taleb calls it “The Tyranny of the Minority”).

The real world is full of examples of this rule. For instance there’s a very small minority of Kosher drinkers in America, but if you look at almost any beverage industrially produced (e.g. Coca-Cola) you can always find a little stamp that certifies the drink is kosher. This happens because this jewish minority deeply cares about this dietary law — they have soul in the game, and they will never compromise on it. Whereas there is a flexible majority who are indeed flexible because most of them probably don’t even know what kosher means… or even if they know, they don’t really care at all. And for the producer, let’s say Coca-Cola, is much easier and cheaper to just make one type of product for everybody — so they just make it all kosher.

A similar story happens with halal meat, where the muslim community is intolerant to non-halal meat — because it’s haram or illegal in their religion — but the majority of people don’t mind eating halal. So the production of halal meat for western countries is significantly overrepresented because of this dynamic of the minority rule. Again, it’s the tyranny of the minority.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Alexander said that it was preferable to have an army of sheep led by a lion than an army of lions led by a sheep. Alexander (or whoever produced this probably apocryphal saying) understood the value of the active, intolerant, and courageous minority. Hannibal terrorized Rome for a decade and a half with a tiny army of mercenaries, winning twenty-two battles against the Romans, battles in which he was outnumbered each time. He was inspired by a version of this maxim. For, at the battle of Cannae, he remarked to Gisco, who was concerned that the Carthaginians were outnumbered by the Romans: “There is one thing that’s more wonderful than their numbers…in all that vast number there is not one man called Gisgo.”

This large payoff from stubborn courage is not limited to the military. “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has,” wrote Margaret Mead. Revolutions are unarguably driven by an obsessive minority. And the entire growth of society, whether economic or moral, comes from a small number of people.

…

Society doesn’t evolve by consensus, voting, majority, committees, verbose meetings, academic conferences, tea and cucumber sandwiches, or polling; only a few people suffice to disproportionately move the needle. All one needs is an asymmetric rule somewhere—and someone with soul in the game. And asymmetry is present in about everything.

So in this context I think it’s easier to understand why Heraclitus wrote “One man is worth thousand if he is extraordinary”, or why Einstein said: “It is important to foster individuality, for only the individual can produce the new ideas.” And if you look at the genesis of the most successful companies you’ll find clear examples of the power of the individual, where the founder has soul in the game and is able to inspire others to follow him on his mission. But if you remove the founder, the whole thing collapses — or at least it collapses in the formation stage of the company.

💡Idea #10: Employee vs. Contractor

Many people believe that running a company with contractors (instead of employees) is much more efficient. Sometimes there is no work to do and if you have employees you still have to pay them. But if you had contractors instead, then you can efficiently meet the demand by only hiring them when it’s necessary.

But there is a problem: contractors behave much more opportunistically than employees. They might get a better offer from a different company and then call you — just 5 hours before the expected time of the service — to let you know that he won’t be able to do his job, which might be catastrophic to your firm.

On the other hand, an employee would almost never let you down. And the reason for this is that the employee has more skin in the game than the contractor. He has much more to lose. An employee is terrified of being fired, whereas a contractor doesn’t mind that much losing one of his clients. And it’s from this fear and potential downside that an employee is significantly more reliable than a contractor.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Employees exist because they have significant skin in the game—and the risk is shared with them, enough risk for it to be a deterrent and a penalty for acts of undependability, such as failing to show up on time. [With an employee] You are buying dependability. And dependability is a driver behind many transactions.

Taleb argues that this is also the reason for why families in Ancient Rome had a slave as the treasurer — the person responsible for the finances of the household. You can inflict a much higher punishment on a slave than a free person, so it’s significantly less likely that the slave would steal from the family or commit errors.

And beyond the employee’s skin in the game in the company, he also has skin in the game in the whole industry…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

People are no longer owned by a company but by something worse: the idea that they need to be employable. The employable person is embedded in an industry, with fear of upsetting not just their employer, but other potential employers.

On this chapter I found one of my favorite lines from the book:

“What matters isn’t what a person has or doesn’t have; it is what he or she is afraid of losing. The more you have to lose, the more fragile you are.”

So one takeaway I got from this idea is that the more perks, money, or status you derive from someone else or from some organization or company, the easier it is to be controlled or owned by others. Because one becomes attached to all these things and then you’ll compromise your personal freedom (and even your moral freedom) to avoid losing those things. In essence, you become a slave — someone who is owned by others.

In my personal case I’m a contractor and an independent content creator, but even if I was an employee (which I was, in the past) I guess my strategy would be to try not to become so attached to these things as to be owned by others. Im reminded of a story of Socrates that I read on a book written by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, where he wrote: “Socrates saw various articles of luxury spread out for sale, he exclaimed: How much there is in the world I do not want.” So I think this attitude helps a lot to not being owned by others. Naval Ravikant also wrote “People who live far below their means enjoy a freedom that people busy upgrading their lifestyles can’t fathom.”

And finally, the decisive trait that will tip the balance to being free or being owned by others is courage. As Seneca wrote: “He who is brave is free.”

💡Idea #11: The Origin of Envy

This idea is not directly related to the theme of skin in the game, but it gave an insightful new perspective on the topic of envy and jealousy and I want to share it with you.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

As with all communist movements, it is often the bourgeois or clerical classes who are the early adopters of revolutionary theories. So class envy doesn’t originate from a truck driver in South Alabama, but from a New York or Washington, D.C., Ivy League–educated IYI (say Paul Krugman or Joseph Stiglitz) with a sense of entitlement, upset some “less smart” persons are much richer.

…

Aristotle, in his Rhetoric, postulated that envy is something you are more likely to encounter in your own kin: lower classes are more likely to experience envy toward their cousins or the middle class than toward the very rich. And the expression Nobody is a prophet in his own land, making envy a geographical thing (mistakenly thought to originate with Jesus), originates from that passage in the Rhetoric. Aristotle himself was building on Hesiod: cobbler envies cobbler, carpenter envies carpenter. Later, Jean de La Bruyère wrote that jealousy is to be found within the same art, talent, and condition.

Another perspective from the book The 48 Laws of Power…

🟠 Robert Greene:

Only a minority can succeed at the game of life, and that minority inevitably arouses the envy of those around them. Once success happens your way, however, the people to fear the most are those in your own circle, the friends and acquaintances you have left behind. Feelings of inferiority gnaw at them; the thought of your success only heightens their feelings of stagnation. Envy, which the philosopher Kierkegaard calls “unhappy admiration,” takes hold. You may not see it but you will feel it someday—unless, that is, you learn strategies of deflection, little sacrifices to the gods of success. Either dampen your brilliance occasionally, purposefully revealing a defect, weakness, or anxiety, or attributing your success to luck; or simply find yourself new friends. Never underestimate the power of envy.

👉 Book: The 48 Laws of Power, by Robert Greene.

One of the best remarks I’ve heard on envy also comes from Charlie Munger, where he said that the world is not driven by greed, it’s driven by envy. And he also mentions that envy is the worst of all sins from Christianity because it’s the only one you can’t even have fun.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

So I doubt Piketty [and here Taleb is referring to the french economist Thomas Piketty, who wrote a famous book on Inequality] bothered to ask blue-collar Frenchmen what they want. I am certain that they would ask for better beer, a new dishwasher, or faster trains for their commute, not to bring down some rich businessman invisible to them. But, again, people can frame questions and portray enrichment as theft, as was done before the French Revolution, in which case the blue-collar class would ask, once again, for heads to roll.

On that line where Taleb says that people can portray enrichment as theft, I was reminded of something that Paul Graham wrote on his book Hackers and Painters…

🟠 Paul Graham:

With the rise of the middle class, wealth stopped being a zero sum game. Jobs and Wozniak didn’t have to make us poor to make themselves rich. Quite the opposite: they created things that made our lives materially richer. They had to, or we wouldn’t have paid for them. But since for most of the world’s history the main route to wealth was to steal it, we tend to be suspicious of rich people.

Idealistic undergraduates find their unconsciously preserved child’s model of wealth [and this model he says it’s a zero sum game model where the money seems to flow from parents and authorities] confirmed by eminent writers of the past. It is a case of the mistaken meeting the outdated. “Behind every great fortune, there is a crime,” Balzac wrote. Except he didn’t. What he actually said was that a great fortune with no apparent cause was probably due to a crime well enough executed that it had been forgotten. If we were talking about Europe in 1000, or most of the third world today, the standard misquotation would be spot on. But Balzac lived in nineteenth-century France, where the Industrial Revolution was well advanced. He knew you could make a fortune without stealing it. After all, he did himself, as a popular novelist.

👉 Book: Hackers and Painters, by Paul Graham.

💡Idea #12: The Lindy Effect

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Lindy is the name of a deli in New York, where actors who hung out there discovered that Broadway shows that lasted for, say one hundred days, had a future life expectancy of a hundred more. For those that lasted two hundred days, two hundred more. The heuristic became known as the Lindy effect.

…

Time is equivalent to disorder, and resistance to the ravages of time, that is, what we gloriously call survival, is the ability to handle disorder… the only effective judge of things is time—by things we mean ideas, people, intellectual productions, car models, scientific theories, books, etc. You can’t fool Lindy: books of the type written by the current hotshot Op-Ed writer at The New York Times may get some hype at publication time, manufactured or spontaneous, but their five-year survival rate is generally less than that of pancreatic cancer.

…

For time operates through skin in the game. Things that have survived are hinting to us ex post that they have some robustness—conditional on their being exposed to harm.

So the key idea of the Lindy effect is that the longer something has survived, the more robust it likely is, and the longer is expected to survive in the future. So as an example, an advice given by a grandmother is much more likely to be true than the latest discovery by a department of Social Sciences.

And even in business it’s extremely valuable to pay attention to the timeless. This is what Jeff Bezos said on this in an interview with Werner Vogels back in 2012:

🟠 Jeff Bezos:

I very frequently get the question: “What’s gonna change in the next 10 years?” And that is an interesting question, it’s a very common one. I almost never get the question: “What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?” And I submit to you that that second question it’s actually the more important of the two… Because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time.

And so as you pointed out in our retail business we know the customers want: Low prices—and I know that’s going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery, they want vast selection—it’s impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up to me and says: “Jeff I love Amazon I just wish the prices were a little higher”, “I love Amazon I just wish you’d delivered a little more slowly”… Impossible!

And so the effort that we put into those things—spinning those things up—we know the energy we put into it today will still be paying dividends for our customers 10 years from now.

And so when you have something that you know is true… even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.

On AWS, the big ideas are also pretty straightforward. It’s impossible for me to imagine that 10 years from now somebody is going to say: “I love AWS I just wish it were a little less reliable” or “I love AWS I just wish you would raise prices… it should be a little more expensive” or “I love AWS and I wish you would innovate and improve the API at a slightly slower rate.” None of those things you can imagine.

And so the big ideas in business are often very obvious but it’s very hard to maintain a firm grasp of the obvious at all times.

But if you can do that and continue to spin up those flywheels and put energy into those things—as we’re doing with AWS—over time you build a better and better service for your customers on the things that genuinely matter to them.

Balaji Srinivasan (CTO of Coinbase and founder of the Network State) also has an interesting take on this. He likes to spend time either in the very old, or in the very new. He argues this is a great source of business opportunities and finding things that are true but that most people don’t know about…

🟠 Balaji Srinivasan:

The newest technical papers and the oldest books are the best sources of arbitrage. They contain the least popular facts and the most monetizable truths. What do you know to be true that others cannot or will not bring themselves to admit? There is your competitive advantage.

I read a lot of old books and new technical journals. I’m less focused on the contemporaneous and more focused on finding things that are true but that most people don’t know. Brian Chesky, founder of Airbnb, learned from a bunch of articles written in the late 1800s about rooming houses. Room sharing was much more popular around 1900 than in 1950. He saw solutions in a sharing economy from a hundred years ago. Then he modernized, transplanted, and used those ideas today. Reading books about societal arrangements at other times and places is a very useful thing.

Technical journals are another source of underappreciated truths. In biomedical papers, you will see that life extension and youth extension for mice is much more advanced than people think. Brain-machine interfaces are also much more advanced than the general public realizes. We have mice telepathically controlling devices. We can do fantastic things with tissue regeneration as well. The technology is here, being held back by the FDA or a lack of distribution.

Technical journals and old books are what I read with intent, as opposed to tech news, which I get in my peripheral vision.

👉 Book: The Anthology of Balaji, by Eric Jorgenson.

♡ An App I’m Loving (not sponsored)

All the way back to 24th December of 2023, I learned about an app that completely changed how I pick insights from YouTube.

It’s called Reader, and (among other features) it lets me seemingly connect any YouTube video to it and watch it on the Reader website (and mobile app).

But… Why would I watch YouTube videos on Reader instead of YouTube?? The answer is simple:

(1) It has a more easy-to-follow transcript of the video.

(2) You can make highlights right inside the transcript! (both in the website or the mobile app). And you can also write notes on those highlights.

Then, the Reader app will create a notebook with all your highlights and notes (from that video), and even connect automatically to Readwise (an app that aggregates highlights from Reader, Kindle, etc.).

This is how I’m building my own personal library of ideas that have resonated with me, which I can revisit at any time.

“A chief part of learning is simply knowing where you can find a thing.”

- Latin Motto

(3) Another benefit is that there are no distractions! You can focus exclusively on the information of the video. This has expanded my attention span…

“I did not succeed in life by intelligence. I succeeded because I have a long attention span.”

- Charlie Munger

There is a free trial of 30 days (after that it’s $9.99 per month), but I reached out to the team at Reader and they made a special offer for us! If you use my special link you will get a 60-day free trial (after that it’s $9.99 per month) 👉 https://readwise.io/pickingnuggets-reader

💡Idea #13: Skin In The Game Breeds Simplicity

Taleb argues that professionals without skin in the game — such as consultants, academics, and economists — tend to overcomplicate things because they are rewarded for perception. Whereas professionals with skin in the game — such as traders, entrepreneurs, and surgeons — seek simplicity because they are rewarded for results…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

People who have always operated without skin in the game (or without their skin in the right game) seek the complicated and centralized, and avoid the simple like the plague. Practitioners, on the other hand, have opposite instincts, looking for the simplest heuristics.

People who are bred, selected, and compensated to find complicated solutions do not have an incentive to implement simplified ones.

…

Many problems in society come from the interventions of people who sell complicated solutions because that’s what their position and training invite them to do. There is absolutely no gain for someone in such a position to propose something simple: you are rewarded for perception, not results. Meanwhile, they pay no price for the side effects that grow nonlinearly with such complications.

The mathematician (and ex hedge fund manager) Edward Thorp also shares a similar take on this…

🟠 Edward Thorp:

For an academic judged by his colleagues, rather than the bank manager of his local branch (or his tax accountant), a mountain giving birth to a mouse, after huge labor, is not a very good thing. They prefer the mouse to give birth to a mountain; it is the perception of sophistication that matters. The more complicated, the better; the simple doesn’t get you citations, H-values, or some such metric du jour that brings the respect of the university administrators, as they can understand that stuff but not the substance of the real work. The only academics who escape the burden of complication-for-complication’s sake are the great mathematicians and physicists.

👉 Book: A Man for All Markets, by Edward Thorp.

The other interesting thing here is that this idea stems from another idea — which is that people will naturally follow their incentives. Probably the best account I’ve read on this comes from Charlie Munger, he calls it the Reward—and punishment—superresponse tendency…

🟠 Charlie Munger:

I place this tendency first in my discussion because almost everyone thinks he fully recognizes how important incentives and disincentives are in changing cognition and behavior. But this is not often so. For instance, I think I’ve been in the top 5 percent of my age cohort almost all my adult life in understanding the power of incentives, yet I’ve always underestimated that power. Never a year passes but I get some surprise that pushes a little further my appreciation of incentive superpower.

One of my favorite cases about the power of incentives is the Federal Express case. The integrity of the Federal Express system requires that all packages be shifted rapidly among airplanes in one central airport each night. The system has no integrity for the customers if the night work shift can’t accomplish its assignment fast. And Federal Express had one hell of a time getting the night shift to do the right thing. They tried moral suasion. They tried everything in the world without luck. And finally, somebody got the happy thought that it was foolish to pay the night shift by the hour when what the employer wanted was not maximized billable hours of employee service but fault-free, rapid performance of a particular task. Maybe, this person thought, if they paid the employees per shift and let all night shift employees go home when all the planes were loaded, the system would work better. And, lo and behold, that solution worked.

👉 Book: Poor Charlie’s Almanack, by Peter Kaufman and Charlie Munger.

As a summary (and to tie these two ideas together): we should always think about the super power of incentives, and whether the person you are dealing with has skin in the game or not. So if the person doesn’t have skin in the game, you know that he or she has an incentive to overcomplicate things — and therefore he will overcomplicate things. And if the person does have skin in the game, you know that he has an incentive to get to the right solution — and therefore he is not gonna overcomplicate things for the sake of giving you a good impression, he is just interested in the outcome rather than the cosmetic appearance of how he gets to the outcome.

A known phenomenon that occurs at the level of incentives, as a result of a lack of skin in the game, is the Agency Problem — which is the next idea.

💡Idea #14: The Agency Problem

The agency problem happens when the agent — for instance the CEO of a company — has a different incentive than the people he is representing — which for the CEO it would be the shareholders of the company.

Taleb illustrates this concept with an experience he had in a conversation with James Cameron when he was running for Prime Minister of the UK. In a short part of the one-hour conversation they had, Nassim explained his Precautionary Principle applied to climate change…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

One does not need complex models as a justification to avoid a certain action. If we don’t understand something and it has a systemic effect, just avoid it. Models are error-prone, something I knew well with finance; most risks only appear in analyses after harm is done. As far as I know, we only have one planet. So the burden is on those who pollute—or who introduce new substances in larger than usual quantities—to show a lack of tail risk. In fact, the more uncertainty about the models, the more conservative one should be.

This is very different to how london newspapers portrayed it. They made it look like Taleb was anti-climate and even called him a “climate denier”. This misrepresentation was due to the fact that they wanted to tarnish the reputation of David Cameron. So in this case the media had a political incentive, and an incentive to not diverge from the narratives of other newspapers — because if you diverge too much you might get fired…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The divergence is evident in that journos worry considerably more about the opinion of other journalists than the judgment of their readers. Compare this to a healthy system, say, that of restaurants. Restaurant owners worry about the opinion of their customers, not those of other restaurant owners, which keeps them in check and prevents the business from straying collectively away from its interests. Further, skin in the game creates diversity, not monoculture. Economic insecurity worsens the condition. Journalists are currently in the most insecure profession you can find: the majority live hand to mouth, and ostracism by their friends would be terminal. Thus they become easily prone to manipulation by lobbyists, as we saw with GMOs, the Syrian wars, etc. You say something unpopular in that profession about Brexit, GMOs, or Putin, and you become history. This is the opposite of business where me-tooism is penalized.

This last part (where Taleb says that undifferentiation is penalized in business) reminded me a line from Jeff Bezos: “Differentiation is survival.” And James Dyson even goes as far as to say “Difference for the sake of it in everything” — which I think is a fantastic line to bias ourselves towards differentiation.

In the business context, the opposite of the entrepreneur who is concerned about the customer, would be an employee in a big corporation who is mainly concerned about his reputation in the firm and on not losing his job — so again here we have the agency problem and a focus on the cosmetic in order to give a good impression to peers and managers. This can also be captured in that popular line about IBM computers, the line goes: ‘No one ever got fired for buying IBM’.

Rory Sutherland (vice-chairman of Ogilvy & Mather and also a good friend of Nassim Taleb) would later comment on this line on his book Alchemy…

🟠 Rory Sutherland:

‘No one ever got fired for buying IBM’ was never the company’s official slogan – but when it gained currency among corporate buyers of IT systems, it became what several commentators have called ‘the most valuable marketing mantra in existence’. The strongest marketing approach in a business-to-business context comes not from explaining that your product is good, but from sowing fear, uncertainty and doubt around the available alternatives. The desire to make good decisions and the urge not to get fired or blamed may at first seem to be similar motivations, but they are, in fact, never quite the same thing, and may sometimes be diametrically different.

👉 Book: Alchemy, by Rory Sutherland.

So in this example from Rory we can see how the employee will pick the suboptimal but conventional choice over the optimal but unpopular one, because if the choice turns out to be bad, he will not get fired if he followed the conventional practice — whereas he might get fired if he picked the uncommon alternative.

💡Idea #15: How To Make (True) Friends

Taleb says that if you wanna build genuine friendships, the relationship can never be hierarchical. Instead, the relationship should be as equals — in what the psychologist Alfred Adler would call a horizontal relationship. And although wealth is an obvious generator of a hierarchical structure, Taleb also talks about a much less obvious generator: your level of erudition…

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Being rich you need to hide your money if you want to have what I call friends. This may be known; what is less obvious is that you may also need to hide your erudition and learning. People can only be social friends if they don’t try to upstage or outsmart one another. Indeed, the classical art of conversation is to avoid any imbalance, as in Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier: people need to be equal, at least for the purpose of the conversation, otherwise it fails. It has to be hierarchy-free and equal in contribution. You’d rather have dinner with your friends than with your professor, unless of course your professor understands “the art” of conversation.

Indeed, one can generalize and define a community as a space within which many rules of competition and hierarchy are lifted, where the collective prevails over one’s interest. Of course there will be tension with the outside, but that’s another discussion.

As I mentioned earlier, the psychologist Alfred Adler also talked about the importance of avoiding all sorts of hierarchical relationships — which he calls vertical relationships. And instead build hierarchical-free relationships — which he calls horizontal relationships. Adler argues that one of the big problems with hierarchical relationships is that it creates a feeling of competition, a feeling that the other person is a rival, and this feeling creates loneliness because you cannot fully trust a rival or root for a rival. In contrast, if you are in hierarchical-free relationships, you will see others as comrades, which creates a feeling of community, which ultimately leads to happiness and peace. If you wanna learn more about Adlerian psychology, I recommend you checking out the book The Courage To Be Disliked.

“Don’t walk in front of me… I may not follow

Don’t walk behind me… I may not lead

Walk beside me… just be my friend.”

- Albert Camus

💡Idea #16: Rationality is About Survival

I found this idea really interesting because it challenges the conventional view on Rationality. The conventional view is to examine a belief in and of itself, and then conclude that it’s rational if it makes sense and is scientifically true, or conclude that it’s irrational if it doesn’t make sense and is false. So what Nassim proposes is that we shouldn’t just examine a belief in and of itself — but go beyond that, and examine also it’s consequence on our survival — and the consequence on our survival should be the only judge as to whether the belief is rational or irrational. Therefore, we cannot say that a belief is rational or irrational in and of itself, instead we can say that it’s rational if the belief helps you survive, or irrational if the belief hinders your survival.

So rationality is also about skin in the game, since we are looking at the real life consequences of beliefs — rather than the pure intellectual domain of the beliefs — to decide whether it’s rational or not.

🟠 Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

The only definition of rationality that I’ve found that is practically, empirically, and mathematically rigorous is the following: what is rational is that which allows for survival. Unlike modern theories by psychosophasters, it maps to the classical way of thinking. Anything that hinders one’s survival at an individual, collective, tribal, or general level is, to me, irrational.

…

Superstitions can be vectors for risk management rules. We have as potent information that people who have them have survived; to repeat, never discount anything that allows you to survive. For instance, Jared Diamond discusses the “constructive paranoia” of residents of Papua New Guinea, whose superstitions prevent them from sleeping under dead trees. Whether it is superstition or something else, some deep scientific understanding of probability that is stopping you, it doesn’t matter, so long as you don’t sleep under dead trees. And if you dream of making people use probability in order to make decisions, I have some news: more than ninety percent of psychologists dealing with decision making (which includes such regulators and researchers as Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler) have no clue about probability, and try to disrupt our efficient organic paranoias.

Taleb’s proposition of rationality reminded me of something I read in the book The Lessons of History written by Will and Ariel Durant…

Will Durant & Ariel Durant:

History remains at bottom a natural selection of the fittest individuals and groups in a struggle wherein goodness receives no favors, misfortunes abound, and the final test is the ability to survive.

Nature and history do not agree with our conceptions of good and bad; they define good as that which survives, and bad as that which goes under.

👉 Book: The Lessons of History, by Will Durant & Ariel Durant.

A few days ago I was listening to a conversation between David Senra (host of the Founders podcast) and Tobi Lutke (founder of Shopify). And I heard Tobi explain the power of Affirmation and how helpful it’s been in his career. So seen from this frame of survival, it is absolutely rational to believe in affirmation because it helps you survive — in this case to survive in business.

Another example is Marc Benioff, who after attending a few of Tony Robins motivational seminars was deeply moved to start his own business. That business is Salesforce and as of today is worth over 200 billion dollars.

“Rationality is avoidance of systematic ruin.” - Nassim Nicholas Taleb

And that’s where I’ll leave it.

I highly recommend buying the book.

And if you prefer something shorter with all the key ideas I recommend you checking out Shortform. I’ve been using Shortform for years and it’s part of my learning funnel: So first I would read many book summaries on Shortform — this is what I call the discovery phase — and when I find one that hooks me, I then buy the book and read it — this is the exploitation phase. But even after reading the book, I would go back to the summary on Shortform to remind myself of the key ideas from time to time — and I do this because repetition is how we learn.

They have a library of over a thousand book summaries — including the whole collection from Taleb — and for each summary they have exercises, an audio version, you can make notes and highlights, and you can even download the book summary as a PDF (so you can read offline and keep it with you). It also comes with an AI browser extension to summarize any article or video on the web.

And by the way Shortform is not sponsoring this blog post, but I do have an affiliate link that can get you a 5-day free trial and an exclusive 20% discount. Just go to shortform.com/almanackbooks

Also, don’t forget to subscribe so you don’t miss future book reviews!

And thank you for reading :)

Great read, can you also publish something like this for THE BLACK SWAN book

Thank you. I have taken notes of this blog in my notebook.