Hello Friend!

Today (April 5th) I’m writing this letter from a nice terrace in the streets of Vienna.

It’s 13:20 pm here as I’m writing these words, and I’m drinking a cup of black tea.

Can’t imagine a better place to write this letter!

Today’s insight comes from Peter Thiel, on the issue of overvaluing competition and popularity and undervaluing substance and mission. It’s from a speech he gave at Stanford in 2014.

👤 Authors

💡Nugget

🟠 Peter Thiel:

Video (source) - Peter Thiel Speech at Stanford (2014)

We (sort of) are taught that competition is valuable. And there's sort of this "safety in crowds"—that if a lot of people are trying to get something, it must be a good thing to do. It's like if there's a long line of people waiting to get in somewhere, you just get in line. You don't even ask why (why people are standing in line).And there is sort of this psychology... Where already in the time of Shakespeare, the word ape meant both primate and to imitate. And there is something about human nature that's ape like, sheep like, lemming like, herd like. We're attracted to these things where a lot of other people are doing them.

I think this is always a challenge (with a lot of the ways we're taught in school and we're educated) where you're taught to compete for all the same credentials. If you're on a Athletic team in high school or college, you're competing on things there.

The competition has the effect of making you better at that at which you're competing. So, if you spend years prepping for an S.A.T. Test, you will get better at taking the S.A.T. Test. Or if you're on a swim team in high school, you'll get better at swimming because you're focused on beating the people around you. But it always sort of comes at this price of possibly losing sight of broader questions, of questions of what's really valuable or what's really important.

There's a crazy line from Henry Kissinger talking about this sort of fellow faculty members at Harvard, where he said:

“The battles in Academia are so ferocious because the stakes are so small.”

And, it always seems like "well, this is (sort of) like a formula for insanity." Why would the battles be so ferocious? If the stakes are small, there's no real need to fight... And so it's just sort of like describing some sort of mass insanity. But on another level, it's also describing the inner logic of a situation where if the stakes are small, if the differences are small, you have to fight much harder to differentiate yourself. And the competition gets more and more intense. And so we end up with these dynamics where everyone tries to go through the same tiny door when maybe there's a huge gate just around the corner that nobody wants to explore. And I think that's sort of the dynamic we're always up against.

There's a version of this phenomenon in Silicon Valley... where it's sort of a strange way... in which there are a lot of people who seem to have Asperger's (or something like that) seem to do really, really well in all these companies. And I always think this should be turned around as a critique of our society where... What does it say about our society where anyone—who's well adapted socially—is talked out of all of their original ideas before they're even fully formed. Because they sort of pick up all these social cues from people...

"Oh that's a little bit too weird... That's strange... Nobody's done that before... Maybe you should not do this..."

And so that the people who are not able to understand what people around them are doing are somehow able to explore some of these original ideas much further.

There's this very strange set of studies that's been done around Harvard, at Harvard Business School, and you can think of sort of business schools as consisting of the anti-Asperger profile of people. So it's people who are extremely extroverted, sort of hyper social, [and] often don't have any really strong convictions (but I won't make this too sweeping a generalization). And you sort of have a hothouse environment where you put all these people in one place for 2 years, and they sort of say: "Well, what do they do at the end? And it turns out (at Harvard they've done these studies over 30 years now) the largest number [of them] always goes into the wrong field—all trying to ride the last wave...

So, [in] 1989 everybody wanted to work for Michael Milken—this was one or two years before he went to jail. No one was ever really interested in internet or tech (technology businesses) except 1999/2000—just as the Dotcom bubble was about to blow up. In the last decade, it was all sort of housing and private equity.

And so there is this really deep dynamic where, even though rationally we should avoid competition and we should aim for monopoly, psychologically we seem to always find it much more comfortable to go with the large crowds of people. But there is no wisdom in crowds. This is an anti-Malcolm Gladwell thing. There's no wisdom of crowds. There's only really ferocious competition.

So, think about this really hard.

“So, concerning the things we pursue, and for which we vigorously exert ourselves, we owe this consideration — either there is nothing useful in them, or most aren’t useful. Some of them are superfluous, while others aren’t worth that much. But we don’t discern this and see them as free, when they cost us dearly.”

— SENECA, MORAL LETTERS, 42.6 (from the book The Daily Stoic, by Ryan Holiday)

Naval Ravikant also poses the question:

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you wanted out of life.”

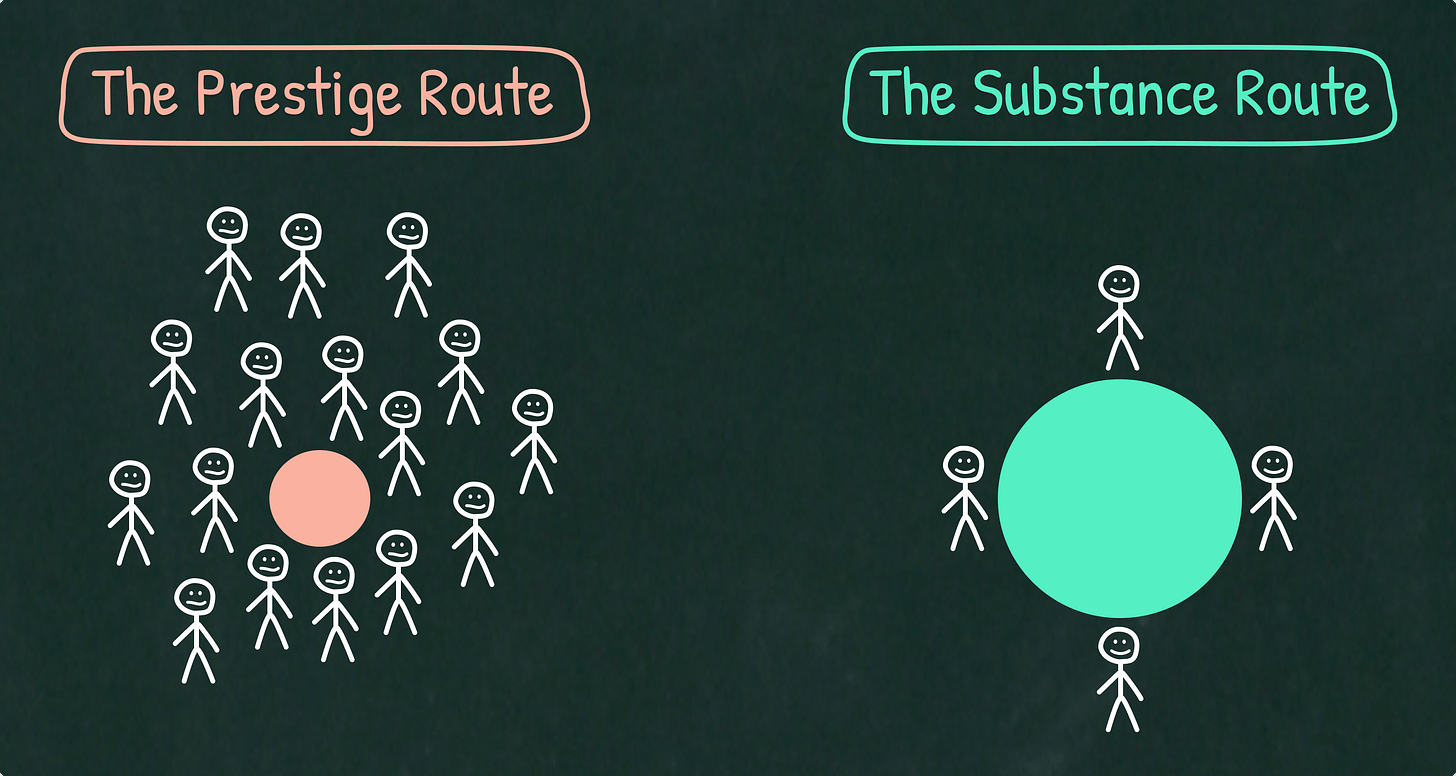

So, you want to be able to get it, but also you want make sure that that's actually what you wanted in the first place! (many people fall into the trap of pursuing unworthy things just because they were blinded by competition and were driven by a status-seeking mindset, where it's more about winning - and the status that that gives them - than actually the substance of what it's won).💥 Stuff I Loved

This Blogpost is brought to you by Shortform - The platform that I love using to get nuggets from Books!

Shortform is THE platform to go if you wanna find highly valuable nuggets (big ideas) from important non-fiction books. This is how I mainly learn from books. Beyond offering book summaries, they provide you with a full guide and synthesis of all the worthy ideas in a book.

Personally, I love it because I can absorb book ideas at a faster pace compared to reading the entire books, and there is a deep analysis on each idea! (it is not shallowly explained, as it is the case in other platforms). But of course, for books that I’m deeply interested in reading I still read the entire book! And then use Shortform to quickly re-visit the main ideas.

I also made a short video exploring the platform and showing you how I’m personally using it. Here’s the Link!

The cost is equivalent to the price of one book a month and you can use my affiliate link to get a 5-Day FREE trial and a 20% Discount on the annual subscription (besides, you will be supporting my work 😉) - shortform.com/pickingnuggets

The mark of a great (non-fiction) author:

“It is my ambition to say in ten sentences what others say in a whole book.”

- Friedrich Nietzsche

A picture of the view when writing this letter…

(the cup of tea was 6 EUR though 😅)

I hope you enjoyed today’s edition! And feel free to send me any feedback or just say hi! (I personally respond to all emails)

Happy Friday ;)

Julio xx

P.S. If you liked this article, you'll definitely enjoy my free 80-page ebook. It’s packed with 23 big ideas (from top influential doers and entrepreneurs) to become better, richer and wiser. Download your copy here!

Great article Julio! I myself have just looked into this and have published an article on group bias. Robert Greene's book The Laws of Human Nature has an excellent chapter on this that you might be interested in.

P.s I hope the tea was worth it :)

Yep... Vienna isn't cheap!